Hussein Longolongo killed seven folks through the 1994 genocide in Rwanda; he oversaw the killing of practically 200 others.

He instructed me this on a heat March day in a courtyard in central Kigali, nearly precisely 30 years later. I had come to Rwanda as a result of I wished to grasp how the genocide is remembered—by way of the nation’s official memorials in addition to within the minds of victims. And I wished to understand how folks like Longolongo look again on what they did.

Longolongo was born in Kigali within the mid-Seventies. As a teen within the late Eighties, he didn’t really feel any private hatred towards Tutsi. He had associates who have been Tutsi; his personal mom was Tutsi. However by the early Nineties, extremist Hutu propaganda had began to unfold in newspapers and on the radio, radicalizing Rwandans. Longolongo’s older brother tried to get him to hitch a far-right Hutu political celebration, however Longolongo wasn’t focused on politics. He simply wished to proceed his research.

On April 6, 1994, Longolongo attended a funeral for a Tutsi man. At about 8:30 p.m., within the midst of the funeral rituals, the sky erupted in pink fireplace and black smoke. The information traveled quick: A airplane carrying the Rwandan president, Juvénal Habyarimana, and the Burundian president, Cyprien Ntaryamira, had been shot down over Kigali. Nobody survived.

Duty for the assault has by no means been conclusively decided. Some have speculated that Hutu extremists shot down the airplane; others have blamed the Rwandan Patriotic Entrance (RPF), a Tutsi army group that had been preventing Hutu authorities forces close to the Ugandan border. Whoever was behind it, the occasion gave Hutu militants a pretext for the bloodbath of Tutsi. The killing began that night time.

Nearly as if that they had been ready for the sign, Hutu militia members confirmed up in Longolongo’s neighborhood. One group arrived at his dwelling and referred to as for his brother. When he got here to the door, they gave his brother a gun and three grenades and instructed him to return with them.

Inside a number of days, a lot of the neighborhood’s Hutu males had been ordered to hitch the hassle. “The directions have been clear: ‘Rwanda was attacked by the RPF, and all of the Tutsi are accomplices. And to defeat the RPF, we’ve to struggle them, but additionally kill all of the Tutsi within the neighborhoods,’ ” Longolongo instructed me. Any Hutu discovered hiding a Tutsi could be thought-about an confederate and could possibly be killed.

The tempo of lethality was extraordinary. Though approximations of the dying toll fluctuate, many estimate that, over the course of simply 100 days that spring and summer time, about 800,000 Rwandans, primarily Tutsi, have been killed.

Longolongo believed that he had no alternative however to hitch the Hutu militants. They taught him the best way to kill, and the best way to kill rapidly. He was instructed that the Tutsi had enslaved the Hutu for greater than 400 years and that in the event that they received the prospect, they might do it once more. He was instructed that it was a patriotic act to defend his nation towards the “cockroaches.” He started to imagine, he stated, that killing the Tutsi was genuinely the proper factor to do. Quickly, he was positioned in command of different militia members.

For Longolongo, the truth that his mom was Tutsi and that he’d had Tutsi associates grew to become a justification for his actions; he felt he needed to make a public spectacle of his executions, to keep away from suspicions that he was overly sympathetic towards the enemy. He feared that if he didn’t reveal his dedication to the Hutu-power trigger, his household could be slaughtered. And so he saved killing. He killed his neighbors. He killed his mom’s good friend. He killed the youngsters of his sister’s godmother. All whereas he was hiding eight Tutsi in his mom’s home. Such contradictions weren’t unusual in Rwanda.

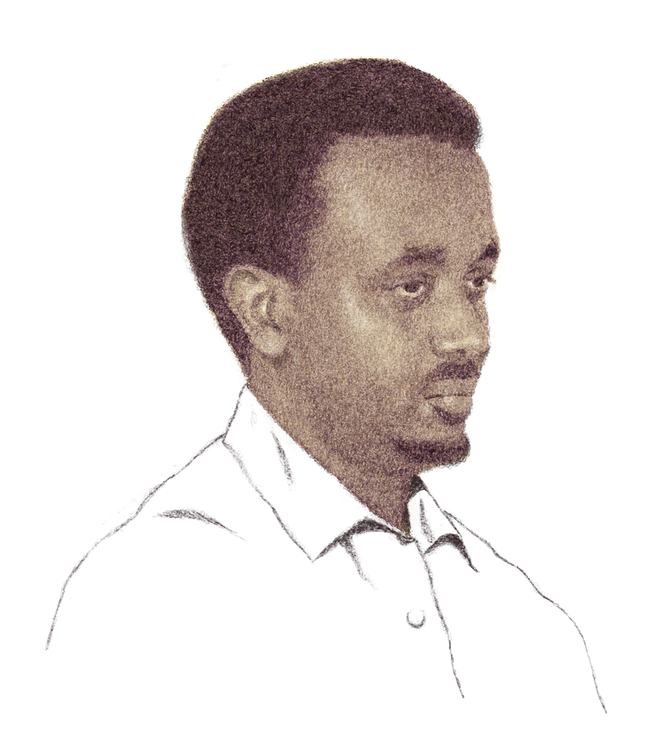

As Longolongo instructed me his story, we have been sitting with Serge Rwigamba, who works on the Kigali Genocide Memorial. Longolongo doesn’t converse English properly, so Rwigamba served as our translator. We saved our distance from others within the courtyard, not sure who may overhear what we have been discussing or how they may react to it.

On April 22, 1994, Longolongo recounted, he and an armed group of males entered a chapel the place dozens of Tutsi have been hiding. “We killed about 70 folks,” he stated, his gaze mounted instantly forward. “I felt prefer it was my responsibility, my accountability … I had no pity.” He put his fingertips to the edges of his head. “I used to be brainwashed.”

After Longolongo received as much as depart, I turned to Rwigamba. He had been visibly uncomfortable at factors through the dialog—wanting down on the floor, his fingers stretching and contracting throughout the arms of his chair as if trying to find one thing to carry on to. Rwigamba is a Tutsi survivor, and dozens of his relations have been murdered within the genocide.

The 2 males, roughly the identical age, had by no means met earlier than. However as Longolongo was talking, Rwigamba instructed me, he’d realized that he acknowledged one of many scenes being described.

It was the chapel. He knew that chapel. Rwigamba himself had been hiding there when Longolongo and his males attacked. His father and brother had been killed that day. Rwigamba had barely escaped. Now he leaned again in his chair, coated his face together with his fingers, and took a deep breath. We sat in silence for a number of moments.

Rwigamba doesn’t deny that propaganda performed an infinite function in persuading Hutu to do what they did. However Longolongo’s empty chair, Rwigamba lamented that he had appeared to push accountability for his actions onto others quite than holding himself accountable. Rwigamba needs perpetrators like Longolongo to acknowledge that they made a alternative. They weren’t zombies. They have been individuals who selected to select up weapons; they have been individuals who selected to kill.

Thirty years have handed since 100 days of violence ravaged Rwanda. Thirty years since machetes slashed, since grenades exploded, since our bodies rotted, since houses burned, since church buildings grew to become slaughterhouses and the soil grew to become swollen with blood. Rwandans are nonetheless residing with the scars of these horrible days. They’re nonetheless studying the best way to calibrate their reminiscences of all that occurred.

In my conversations with dozens of Rwandans this 12 months, I noticed how profoundly the genocide continues to form the lives of the individuals who lived by way of it. There are individuals who protected their neighbors and individuals who introduced machetes down on their neighbors’ heads. There are individuals who hid household of their houses and individuals who handed household over to the militia. There are individuals who killed some so they might shield others. Survivors’ recollections of these horrifying days are directly contemporary and fading. Questions of whom and the best way to forgive—of whether or not to forgive in any respect—nonetheless weigh closely.

Over the previous decade, I’ve traveled to dozens of web sites all through America and around the globe to discover how crimes towards humanity are memorialized. Rwanda has among the most graphic websites of reminiscence I’ve ever seen, locations the place the ugly actuality of what occurred is on show in typically stunning element. And it’s totally different from different websites I’ve visited in one other essential respect: In most of these locations, few, if any, survivors are left. Right here, tons of of hundreds of people that survived the genocide are nonetheless alive to inform the story, and Tutsi and Hutu reside alongside each other as neighbors. I wished to grasp what public reminiscence of an atrocity appears to be like like when the perpetrator and the sufferer proceed to stroll previous one another day-after-day. I wished to grasp whether or not true forgiveness is even doable.

A number of days earlier than we met Longolongo, Rwigamba had proven me across the Kigali Genocide Memorial, which opened in 2004. The memorial sits on a hill that’s stated to carry the stays of 250,000 folks, buried in columns of caskets that descend deep into the earth. Some caskets comprise the stays of a whole household. The cranium of a mom is perhaps sitting alongside the rib cage of her husband, the tibia of her daughter, and the femur of her firstborn son. The graves are coated by huge rectangular blocks of concrete, ornamented in garlands of pink and pink roses positioned by guests.

Rwigamba works as a information and coordinator on the memorial, and likewise serves as vice chairman of the Kigali chapter of Ibuka, a civic group that works to make sure that survivors of the genocide obtain social, political, and financial assist. All through my journey, he served as my translator and information. He was 15 years previous in 1994. He misplaced greater than 50 members of his household, a few of whom are buried on the memorial website. After the genocide, he recalled, his trauma felt suffocating. Daily, he awakened after one other cycle of nightmares and thought of his household. He missed them intensely. “Working right here was considered one of my methods to get near them,” he instructed me.

We walked across the museum on the middle of the memorial, which outlines the historical past that preceded the genocide and highlights images and tales of people that have been killed. The objective is to reveal who they have been in life, to not merely present them as corpses. However what stayed with me was the omnipresent sense of dying. One room shows rows of skulls of people that have been murdered.

We heard wailing, and Rwigamba went to see what was occurring. When he returned, he defined {that a} survivor was visiting the memorial to see her father’s resting place. When she walked by way of the room of skulls, she broke down. Members of the museum’s employees went to consolation her. Rwigamba instructed me that this type of factor occurs typically. As we walked again outdoors, the sound of the lady’s screams echoed by way of the halls.

Rwigamba stated that within the 16 years since he began working on the memorial, he has realized extra about the way in which Hutu extremists used propaganda earlier than and through the genocide. It made him surprise. “I saved on eager about what might have occurred if I used to be born a Hutu. What would have occurred to me?”

Anti-Tutsi propaganda was in all places within the early Nineties, deepening Hutu’s suspicions of their Tutsi neighbors. In December 1990, an extremist Hutu newspaper had printed the “Hutu Ten Commandments,” which referred to as for Hutu political solidarity and said that the Tutsi have been the frequent enemy.

The roots of this antipathy went again a very long time. Earlier than Germany and later Belgium colonized Rwanda, those that owned and herded cows have been usually thought-about Tutsi, and those that farmed the land Hutu. Underneath colonialism, nevertheless, these permeable class boundaries grew to become mounted, racialized markers of identification, and far of the majority-Hutu inhabitants (together with the Twa, a gaggle that made up 1 % of the inhabitants) lived in relative poverty, beneath the management of an elite Tutsi political class. This inequality opened deep fissures: The anthropologist Natacha Nsabimana has written that “the violence in 1994 should be understood as a part of an extended historical past that begins with the racial violence of modernity and European colonialism.”

As animosity towards the Tutsi grew within the mid-Twentieth century, Belgian colonial powers began to position members of the Hutu inhabitants in cost. Within the years earlier than and after Rwanda gained independence, in 1962, Hutu authorities forces killed hundreds of Tutsi. Lots of of hundreds extra Tutsi fled the nation.

Tutsi exiles intermittently attacked Rwanda’s Hutu all through the Nineteen Sixties. Within the late ’80s, hundreds of exiles joined the Rwandan Patriotic Entrance, which invaded Rwanda from Uganda in 1990, setting off a civil struggle. In 1992, beneath worldwide stress, President Habyarimana and the RPF negotiated a cease-fire, and the 2 sides started understanding a peace settlement. Hutu extremists, who noticed the settlement as a betrayal, doubled down on selling anti-Tutsi lies.

Rwigamba gazed out over the memorial’s courtyard, recalling the messages that Hutu acquired from the federal government and the media in these years. “What if I’d have been approached with a lot stress—from society and from my schooling? Hatred is an ideology and is taught in any respect ranges of the society and all ranges of neighborhood. So it was so exhausting for a kid of my age to do one thing totally different.” Rwigamba paused. He appeared like somebody who had missed a flip and was attempting to see if they might again up. “I don’t wish to give an excuse for the individuals who dedicated the genocide,” he stated, “as a result of they’ve killed my household. However I might truly attempt to be taught some type of, , like, empathy, which permits you to consider the opportunity of forgiveness.”

Nonetheless, Rwigamba instructed me, figuring out with the killers in any method, whilst a thought train, can really feel shameful. One other a part of him believes I don’t need to put myself within the footwear of perpetrators. I’m a sufferer! That, he says, is “the simplest method to deal with your wounds”—however maybe not the proper one.

After the genocide, Rwigamba went to high school with the daughter of one of many commanders who oversaw killings in his neighborhood; they sat in the identical classroom. He knew that it wasn’t her fault, that she herself had not held the machetes. However, he questioned, did she carry the identical beliefs as her father? Did she take heed to his tales with admiration? Did she dream of ending his work? For a very long time, Rwigamba stated, his classmate’s presence was a reminder of all that he had misplaced, and all that could possibly be misplaced if historical past have been to repeat itself.

Years later, nevertheless, after Rwigamba encountered his former classmate at church, he selected to place these ideas out of his head. He instructed himself that she was not there to torment him, and he moved on. The scholar Susanne Buckley-Zistel refers to this phenomenon as “chosen amnesia,” describing it as a method for members of a neighborhood to coexist regardless of having had essentially totally different experiences through the genocide. Throughout Rwanda, day-after-day, for 30 years, many individuals have chosen amnesia.

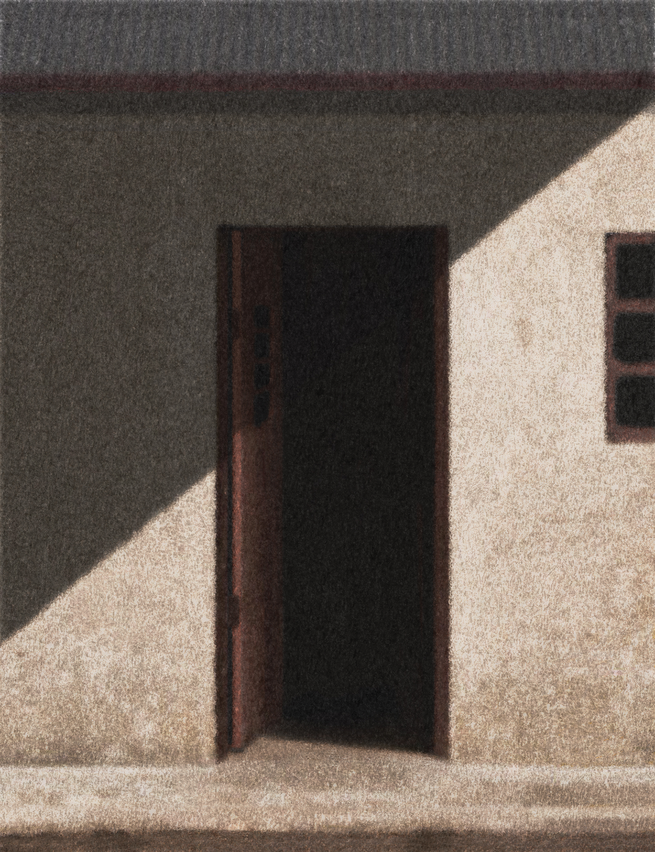

The facade of Sainte-Famille Church in Kigali is adorned with vermilion-colored bricks and white-tile pillars that kind the form of a cross. On the day Rwigamba and I visited, a priest wearing white held a microphone, his voice swelling in a wave of Kinyarwanda because the congregation nodded at his sermon. We sat down in a mahogany pew in the back of the church, and Rwigamba pointed a number of rows forward of us. “I hid beneath that bench for 2 months.”

After the genocide started, Hutu militiamen confirmed up at Rwigamba’s dwelling and instructed his household that they have been going to kill them. They instructed them to kneel down on the bottom. Everybody did as they have been instructed, aside from Rwigamba, who was so afraid, he couldn’t transfer. His father started praying; his mom cried. The lads cocked their weapons and pointed them at his household. “Then, immediately, they stopped,” Rwigamba stated. The lads instructed them that they might allow them to reside, for now, if the household paid them. So Rwigamba’s dad and mom scrounged collectively all they might. “They left us, however with the promise of coming again and ending us off,” Rwigamba stated. Nobody waited round to search out out in the event that they have been telling the reality.

As the times wore on, Rwigamba and his household moved from place to position, typically at a second’s discover. Ultimately, they hid within the chapel that Longolongo and his crew attacked. Quickly after that, Rwigamba and his sister and mom discovered themselves in one other a part of city, at Sainte-Famille Church, which housed hundreds of Tutsi through the genocide.

Church buildings have been a well-liked hiding place: Greater than 90 % of all Rwandans have been Christian, and many individuals hoped that the militia wouldn’t assault areas that have been sacred to each Hutu and Tutsi alike. Some Hutu who had been caught within the crossfire between Hutu forces and the RPF additionally sought refuge in church buildings. Consequently, at Sainte-Famille, Rwigamba and his household sheltered aspect by aspect with the households of the folks attempting to kill them.

Father Wenceslas Munyeshyaka, a priest at Sainte-Famille, would quickly develop into notorious. He traded his clerical gown for a flak jacket, carried a pistol, and, in response to a number of witness accounts, personally handed over Tutsi to the Hutu militia. Day after day, the militia confirmed up with an inventory of names of Tutsi who have been believed to be searching for refuge within the church. Rwigamba acknowledged lots of the killers from his neighborhood—boys and younger males he had gone to high school with. Daily he watched folks get killed, sure that he could be subsequent. The carnage went on for greater than two months. Lots of of Tutsi have been killed; many ladies have been raped. (The United Nations estimates that as much as 250,000 girls have been raped within the genocide; one other estimate places the quantity even greater.)

Throughout a pause within the church service, Rwigamba and I slid out of our seats and stepped outdoors, into a light-weight rain. About 50 yards away was a black-marble wall with rows of names inscribed on either side. Rwigamba bent down and pointed to the daring white letters of two names: Emmanuel Rwigamba and Charles Rwigamba. His elder brother and his father, who have been murdered by Hutu militia members, then thrown right into a mass grave close by.

“This was suffering from corpses of people that had been killed and left right here,” Rwigamba stated, gesturing towards Sainte-Famille’s parking zone.

He pointed to a different spot, to the left of the church, the place he remembers watching the Hutu militia drive a person to dig his personal grave earlier than they shot him and threw him into it.

“I really feel so fortunate to have survived,” Rwigamba stated. “Once we have been transferring round these skulls and bones on the museum, I typically felt like I might have been considered one of them.”

He appeared again on the church entrance as folks started submitting out. “Possibly the people who we have been seeing within the museum—perhaps they have been the identical people who have been with me right here.”

on the Murambi Genocide Memorial Centre, I smelled the lifeless earlier than I noticed them.

Dozens of embalmed our bodies have been laid out throughout two rows of tables on both aspect of the room. I walked towards the again of the room and stopped in entrance of a physique whose proper arm dangled over the sting of the desk. The lady’s head was turned to the aspect. Her mouth was ajar, revealing half a row of uneven tooth on the underside. Her pores and skin, swathed in powdered lime that had turned it a haunting white, was sunken in between her ribs. Her toes have been curled and her left hand had been positioned above her head, as if she have been trying to guard herself from one thing above. There was a rosary round her neck, the crucifix at relaxation close to her chin. A black patch of hair was nonetheless current on the again of her head. Beneath it, a gap in her cranium from the place a machete had cracked it open.

The Murambi memorial sits on the positioning of a former technical college. In April 1994, a gaggle of native leaders satisfied the Tutsi within the space that they might discover safety right here; the Centre estimates that, inside two weeks, 50,000 Tutsi had gathered. However it was a entice.

Quickly the college and the hill it sat atop have been surrounded by a number of hundred males. They threw grenades and shot bullets into the group, then attacked those that have been nonetheless alive with golf equipment and machetes. Hundreds have been killed (the precise quantity stays contested). The victims have been tossed into mass graves, however some have been later exhumed and placed on show as a part of the memorial. In the present day, these mass graves are coated with grass, and the college’s two dozen lecture rooms function the centerpiece of the memorial.

Leon Muberuka, a Tutsi survivor who works as a information right here, accompanied me by way of every classroom. Muberuka was 11 when the genocide occurred. He remembers every part: the our bodies on the bottom, the stench of dying. He nonetheless finds it troublesome to spend time in these lecture rooms. I did too.

Once we stepped outdoors, Muberuka noticed me rubbing my nostril, trying to expel the lingering scent of the our bodies from my nostrils. “This place, within the morning, the odor could be very, very, very exhausting,” he stated. “We shut the door at night time, and once we open it—” He widened his eyes, held his nostril, and exhaled by way of his mouth.

We walked to a constructing on the far finish of the compound. As I crossed the brink, I paused. In entrance of us, inside cylindrical glass tubes, I noticed about 20 corpses that have been higher preserved than those I had simply seen. Many of those our bodies have been brown quite than white. Their pores and skin appeared nearer to what it might need appeared like in life. I walked towards the again of the room. In a single encasement have been two babies. I appeared down at a placard and skim the primary two sentences:

The younger boy died due to a large assault to the top. The cranium lies open and exhibits the nonetheless preserved mind.

The kid, who appeared to have been about 5, wore a light-blue shirt with a pink elephant on the entrance. His mummified eyes have been nonetheless seen, although sunken into his head. I stepped to the left and appeared down on the gap in his cranium. I leaned ahead, and I noticed the kid’s mind.

I went outdoors to gather myself. Seeing this made the horror of the genocide extra actual; it left me feeling a mixture of shock, despair, and rage—each deeply moved and profoundly unsettled. I thought of different memorial websites I’ve visited. After the Holocaust, Allied troopers discovered hundreds of our bodies in barracks, fuel chambers, crematoria, and prepare vehicles. What if a few of these our bodies had been preserved and put in a museum? What if I’d walked into Dachau and seen the our bodies of Jewish individuals who had been murdered on show inside fuel chambers? Would that not compromise the dignity of the lifeless? Or was placing the total, ugly actuality on show like this a method to make sure that folks would proceed to respect its gravity? After I traveled to Germany a number of years in the past, one man I interviewed, the kid of Holocaust survivors, described his repugnance at the truth that, nowadays, folks take selfies at locations like Auschwitz and Dachau. Certainly, given what was being proven right here, nobody would dare do the identical?

Exterior, a yellow-orange solar set behind the encompassing hills. On the three-hour drive north to Murambi, I had marveled at the fantastic thing about these rolling hills, coated within the thick leaves of banana timber. I’d handed girls within the valleys under bending over rice paddies, dipping their fingers into the shallow water; males sweating as they walked bikes uphill, jugs of water strapped to the seat; youngsters in flip-flops chasing soccer balls in entrance of retailers the place the odor of candy potatoes hung within the air.

Seeing the our bodies helped me image the roads that wrap round these hills blocked by machete-wielding males, the land stuffed with the lifeless and dying. As an alternative of smelling candy potatoes if you rolled down your window, I noticed, you might need smelled corpses rotting beneath the solar.

To Muberuka, the vividness is precisely the aim of a memorial like this one, as uncomfortable as it could be. “That is our previous, and everybody must know this,” he stated.

“Typically folks can say the genocide didn’t occur in Rwanda,” Muberuka added, his forehead wrinkling in indignation, alluding to those that declare that the violence was not a genocide however a manifestation of long-standing, two-sided ethnic and tribal battle. “By this proof, it’s actual,” he stated. “In order that’s why, for me, it’s necessary to protect this memorial and a few bodily proof.”

Muberuka’s dad and mom and sister have been killed within the genocide. Or not less than he thinks they have been—he by no means discovered their our bodies. “I don’t know the place they’ve been buried,” he stated. He paused and appeared down. “I don’t know if they’re buried or not.” A gust of wind whistled between us. “If you bury somebody … he’s lifeless. However should you don’t know—” He checked out me, then up on the sky. “Even now, we’re nonetheless ready. Possibly we are going to see them.”

Rumors swirled round his neighborhood. Folks instructed Muberuka that that they had seen his sister, who was a child on the time of the genocide. What if she had been picked up by a household and introduced throughout the border to Uganda? Possibly she was in Kenya.

I requested if he thought she may nonetheless be alive.

“I don’t assume so,” he stated softly. “Thirty years, it’s simply …” His voice trailed off.

For many years, Muberuka had held on to hope. However it was a torturous existence. He noticed this hope torture these round him as properly. He knew individuals who—15, 20, 25 years after the genocide—would stroll as much as a stranger available in the market and seize their face, pondering they is perhaps a long-lost sibling, daughter, or son.

He determined that he needed to let go, or he might by no means transfer ahead. Right here, once more, was this concept of chosen amnesia. It was in all places. In the present day, although he works on the memorial, Muberuka and his surviving siblings don’t focus on the genocide with each other; he says it’s simpler that method.

One other studying of the Murambi Genocide Memorial Centre and equally graphic websites is that they’re an outgrowth of the Rwandan authorities’s want to strengthen its energy and management. Paul Kagame, previously the Tutsi army chief of the RPF, grew to become president of Rwanda in 2000, and he continues to occupy that workplace at this time. In some respects, he has been an enormously profitable chief. Lots of the Rwandans I spoke with praised him as a singular determine who has, by way of his insistence on reconciliation, managed to forestall one other genocide.

However the nation’s relative stability throughout his time in energy has not been with out prices. Worldwide observers have labeled Kagame an authoritarian. His tenure has been marked by allegations of human-rights abuses towards political opponents, journalists, and activists. In 2015, the USA authorities urged Kagame to step down to permit a brand new technology of Rwandans to guide the nation. Freedom Home, a watchdog group based mostly within the U.S., stated in a 2022 report that Rwanda is “not free.” The federal government, it stated, had been “banning and repressing any opposition group that might mount a severe problem to its management.” In July of this 12 months, Kagame was reelected to a fourth time period. Rwanda’s Nationwide Electoral Fee stated that he acquired 99.2 % of the vote.

The political scientist Timothy Longman argues that websites like Murambi function a warning to Rwandans from the Kagame regime: That is what we put an finish to, and that is what might occur once more if we’re not cautious—if we’re not in cost. Longman is a professor at Boston College and the creator of Reminiscence and Justice in Publish-genocide Rwanda. He spent years residing within the nation as each a scholar and a discipline researcher for Human Rights Watch. He understands the impulse to create memorials that drive guests to confront what occurred, he instructed me, and he shares the view of many Rwandans that the our bodies function a reminder to the world of how profoundly it failed to return to Rwanda’s help. Nonetheless, he finds the show stunning and horrific—a calculated try on the a part of the Kagame regime to maximise guests’ misery on the expense of the victims’ dignity. Utilizing the our bodies to impress a response, he believes, compromises the positioning’s capacity to meaningfully honor the lifeless.

“If the survivors had designed these websites, there wouldn’t be our bodies,” Longman stated. In his guide, he writes a couple of dialog he had with a nun who had survived the genocide: “It’s not good to go away the our bodies like that,” she stated. “They should discover the means to bury them.” However Longman additionally writes in regards to the perspective of one other nun whose sentiments echoed what I heard from Muberuka. “It has one other function,” she stated. “It helps to indicate those that stated that there was no genocide what occurred. It acts as a proof to the worldwide neighborhood.”

When Longman and I spoke, I instructed him how moved I had been by the tales that the survivors shared with me on the numerous websites I’d visited, whilst I used to be cognizant of the truth that the memorials have been finally accountable to the state. Longman thought-about my level. “For the survivors at these websites, it’s their job,” he replied rigorously. “They’re not telling a inventory story, however however, they’re telling their story day-after-day. I don’t assume there may be insincerity, however folks know on some degree what they’re imagined to say, and specifically they know what they can’t say. It doesn’t imply it’s unfaithful, however as with something in Rwanda, dialog is at all times constrained since you’re in an authoritarian context, and there are penalties should you say the incorrect factor.”

On July 4, 1994, after practically three months of violence, RPF forces took management of Kigali, forcing the Hutu militia out of the town. Because the RPF moved by way of Rwanda, practically 2 million Hutu fled to neighboring nations. Within the months and years to return, the transition authorities confronted a query: The best way to obtain justice for victims whereas additionally advancing the objective of reconciliation?

Ultimately, greater than 120,000 Hutu have been arrested on costs of collaborating within the genocide. Rwandan prisons have been overcrowded and teeming with illness. One of many tens of hundreds of Hutu prisoners was Hussein Longolongo. In jail, he was pressured to participate in a government-sanctioned reeducation program. He initially dismissed a lot of what he heard in this system as Tutsi propaganda. “However as time went on, I grew to become satisfied that what I did was not proper,” he instructed me.

Longolongo additionally participated in additional than 100 of what have been referred to as gacaca trials. Gacaca—which roughly interprets to “justice on the grass”—had traditionally been utilized in Rwandan villages and communities to settle interpersonal and intercommunal conflicts. Now the federal government remodeled the function of the gacaca court docket to deal with allegations of genocide.

Witnesses would current an account of an alleged crime to community-elected judges, who would assess its severity and decide the suitable penalties. As a result of 85 % of Rwandans have been Hutu, the judges have been overwhelmingly Hutu. “Numerous gacaca was truly in regards to the Hutu neighborhood themselves attempting to return to phrases with what Hutu had carried out,” Phil Clark, a political scientist who has written a guide in regards to the gacaca courts, instructed me. “It was Hutu judges, Hutu suspects, and sometimes Hutu witnesses doing a lot of the speaking. And genocide survivors typically have been a bit reluctant to get overly concerned for that purpose.”

The courts convened for a decade, from 2002 to 2012. There have been many delays, however for years at a time, all neighborhood members have been required to attend weekly trials. By 2012, greater than 12,000 gacaca courts, involving 170,000 judges, had tried greater than 1 million folks. Nothing like this had ever been carried out on such a big scale wherever else on the earth.

The legacy of the trials is combined. “The courts have helped Rwandans higher perceive what occurred in 1994, however in lots of instances flawed trials have led to miscarriages of justice,” Daniel Bekele, then the Africa director at Human Rights Watch, stated in 2011 when the group launched a report on the gacaca course of. If the trials helped some survivors discover a sense of closure, they reopened wounds for others. They have been typically used to settle scores. In some instances, Tutsi survivors, eager to precise vengeance on Hutu as a gaggle, made false accusations. Though the general public setting of the trials was supposed to make sure transparency, it additionally made some potential witnesses unwilling to testify. And many individuals stayed silent even once they believed {that a} defendant was harmless, afraid of the backlash that may come from standing up for an accused perpetrator.

Some observers objected to the truth that solely crimes towards Tutsi victims have been introduced in entrance of the courts, whereas crimes towards Hutu have been missed. “The genocide was horrible; it was severe, and justice completely needed to be carried out,” Longman instructed me. “However it doesn’t imply that struggle crimes and crimes towards humanity dedicated by the RPF needs to be fully ignored.”

Rwigamba instructed me that he didn’t assume the method was excellent. However he noticed it as essentially the most sensible and environment friendly option to obtain a semblance of justice on an inexpensive timeline. He additionally appreciated that it drew on traditions and practices that have been created by Rwandans quite than counting on judicial mandates imposed by outsiders. “Gacaca taught us that our traditions are wealthy and our values are robust,” he stated.

Longolongo, for his half, discovered that means within the alternative to return face-to-face with the households of these he had helped kill—to confess to his crimes, and to apologize. I requested him if his conscience is now clear. “I really feel so relieved,” he stated. He instructed me that he grew to become associates with lots of the surviving relations of Tutsi he had killed after he confirmed them the place the our bodies of their family members had been discarded. “I really feel like I fulfilled my mission,” he stated.

This revelation took me aback. “You imply you are actually associates with among the folks whose family members you killed?”

Longolongo nodded and smiled. “After realizing that I used to be real and telling the reality, I’ve received so many associates.”

I questioned if associates was the phrase that these Tutsi would use to explain the connection. I considered a remark made by a genocide and rape survivor within the 2011 Human Rights Watch report: “That is government-enforced reconciliation. The federal government pressured folks to ask for and provides forgiveness. Nobody does it willingly … The federal government pardoned the killers, not us.”

On the way in which again to my resort in Kigali one night, I spoke with my driver, Eric (given the delicate nature of his feedback, I’m utilizing solely his first identify). Eric is Rwandan, however he was born in Burundi. His household, like many different Tutsi on the time, left Rwanda in 1959 to flee violence by the hands of Hutu extremists. They returned in 1995, after the genocide ended.

I had learn that, after the genocide, the RPF—now the ruling political celebration in Rwanda—formally eradicated the classes of Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa on the grounds that they have been false variations imposed on Rwandans by colonial powers, classes that had solely led to battle and bloodshed. There have been no extra ethnic classes, the federal government stated, solely Rwandans. I used to be curious how Rwandans determine at this time, whatever the authorities’s directive, and I requested Eric about this.

“A few of them nonetheless determine. You possibly can’t cease that. Some folks nonetheless have that ideology. But in addition, it’s not one thing that’s official.” He paused and commenced to talk once more, then stopped abruptly. “It’s not allowed.” As he talked, I noticed that, privately, Eric nonetheless appeared to assume by way of Tutsi and Hutu.

“I reside along with somebody who was in jail for 18 years. Somebody who killed folks. I do know him,” Eric stated. “He’s my neighbor.” Eric instructed me he doesn’t really feel offended at this man—he has even employed him to do development work on his home, and has had the person’s youngsters do small duties for him.

However as Eric went on, I seen that he appeared to see this as a gesture of generosity, and a method of exhibiting the Hutu that Tutsi are superior—that regardless of what the Hutu did to the Tutsi, the Tutsi have been nonetheless keen to assist them. That they might by no means do to the Hutu what the Hutu did to them, as a result of they’re extra advanced.

Would you say that you simply’ve forgiven him? I requested.

“Yeah. I’ve forgiven him,” Eric stated, nodding. However then he reconsidered. “You realize, you may’t say that you’ve forgiven him 100%, however it’s important to transfer on,” he stated. “We’re not like them.”

I used to be struck by the feel of Eric’s voice when he stated “them.” It was laced with a bitterness I had not but encountered throughout my time in Rwanda. “Naturally, Tutsi and Hutu usually are not the identical of their hearts,” he continued. “You will notice. We’re not the identical. They’ve one thing unhealthy of their hearts. They’re naturally doing unhealthy. That’s how they’re.

“We depart them alone,” Eric stated. “We give them what we’re supposed to offer them. We attempt to reside—to outlive, to reside with them. That’s it. That’s all. Nonetheless, we’ve to watch out, as a result of we’re not certain if their hearts have modified.

“Thirty years shouldn’t be sufficient to belief them,” he continued. “We work collectively. We reside collectively. However we don’t belief them.”

Albert Rutikanga was 17 when President Habyarimana’s airplane was shot down. He heard the information on the radio and ran to inform his father. “We might be killed,” his father stated.

The following day, Hutu started burning Tutsi houses in his village, Rukara. His household rapidly fled to the native church, the place he and I now stood. On April 8, 1994, Rutikanga instructed me, militia members arrived, screaming, with weapons and machetes in hand. They surrounded the church. They threw grenades and shot bullets by way of the open home windows. Waves of assaults continued for days.

Rutikanga pointed to a pew on our proper. “My dad was sitting right here and he was studying a Bible; that’s how he was killed.” His mom died within the assaults as properly. Rutikanga was struck by shrapnel from the grenades thrown into the church. He lifted his pant leg to disclose a big cavity within the flesh of his thigh.

Quickly, the RPF arrived within the village and the Hutu militia fled, abandoning tons of of lifeless Tutsi. Rutikanga didn’t step foot within the church once more for 15 years.

Ultimately he grew to become a high-school trainer. He typically introduced his college students on day journeys to the genocide memorial in Kigali. They have been moved by the memorial, however he got here to suspect that they didn’t totally perceive what had occurred in 1994. There had been so a few years of silence. The scholars’ dad and mom, Rutikanga realized, weren’t having sincere conversations in regards to the genocide with each other or with their youngsters. He determined that he would attempt to recruit survivors to have interaction in direct discussions with perpetrators.

Many survivors have been initially reluctant. “They might say, ‘Are you silly? How are you going to forgive these folks once they killed our household?’ ” Rutikanga instructed them that these conversations weren’t one thing they need to do for the perpetrators. “Forgiveness is a alternative of therapeutic your self,” he would say. “You can’t hold the anger and bitterness inside, as a result of it’s going to destroy you.” Forgiveness, he stated, is the selection of surviving once more.

Rutikanga discovered it simply as troublesome to recruit perpetrators. “They didn’t belief me,” he stated. In 2016, he approached Nasson Karenzi, who, at 30, had been a part of the militia that attacked the church the place Rutikanga and his household have been hiding. Later, whereas in jail, Karenzi confessed to his crimes in a letter he handed to the authorities. He was finally launched.

Karenzi was skeptical at first. What if the conversations triggered even deeper rifts? However he shared Rutikanga’s sense that one thing wanted to be carried out to foster deeper belief and reconciliation throughout the neighborhood, and he agreed to speak with different former perpetrators about collaborating. As soon as that they had about 20 folks, perpetrators and survivors alike, Peace Schooling Initiative Rwanda was born.

In the course of the group’s first conferences, facilitated by an outdoor mediator, everybody treaded rigorously. Folks have been cautious of unveiling an excessive amount of, of opening previous wounds when the one who was chargeable for creating these wounds—or the one who had been pressured to hold them—is perhaps sitting instantly throughout from them. However slowly, the discussions grew to become extra susceptible.

Folks started to inform their family and friends in regards to the group, now referred to as PeacEdu, and extra joined. In the present day, 1,400 adults within the village have participated in PeacEdu workshops, and the group has reached 3,500 younger Rwandans by way of its school-based programming.

PeacEdu’s workplace is a small concrete constructing with yellow partitions and French doorways that open onto a backyard courtyard. There, I met with 4 individuals in this system. The 2 girls, Francoise Muhongayire and Clementine Uwineza, have been survivors of the genocide. The 2 males, Karenzi and Francois Rukwaya, had participated in it.

Rukwaya had a bald head that caught the sunshine from above; he wore a checkered inexperienced oxford shirt that appeared a dimension too massive. The very first thing he instructed me was that he had killed eight folks in a single assault, early on within the genocide. He was 27 in 1994, and was later imprisoned. He, too, wrote a confession, and was later launched. (Kagame has freed hundreds of prisoners en masse on a number of events.)

Muhongayire wore a green-and-gold costume, with frills that bloomed from the shoulder. She had a big Afro and spoke in lengthy sentences that rose and fell just like the hills round us. She recounted working from the militia and hiding in a swamp the day the genocide started. When she returned to seek for her household, she discovered her dad and mom and eight of her siblings lifeless. She and a gaggle of different Tutsi hid in a home the place they thought they is perhaps protected. However the militia discovered them, poured gasoline on the home, and set it on fireplace. The house was engulfed in flames and nearly everybody inside died. Muhongayire barely escaped. She nonetheless carries scars from the burns.

“I lived a depressing life after,” she stated. “I had nobody. I used to be residing with a lot despair. Till I noticed Karenzi, who got here towards my home. And once I noticed him, I instantly ran away and tried to cover as a result of that triggered me and made me assume that he was coming to assault us.”

Karenzi got here again repeatedly, every time asking for forgiveness. At one level, Muhongayire instructed him that she forgave him simply so he would cease bothering her. However she didn’t imply it.

Not lengthy after, Rutikanga approached her about becoming a member of his new initiative. Muhongayire wished no half in it. These folks had killed her total household. How might she look them within the eye? Forgive them? No probability. Lastly, Rutikanga persuaded her to offer it a attempt. She might at all times stand up and depart if it grew to become too troublesome.

But as she listened to Karenzi and others clarify what had led them to commit violence and listened to them apologize, genuinely, for all that they had carried out, Muhongayire might really feel one thing altering inside her. On the time, she had a coronary heart situation that medical doctors couldn’t precisely diagnose or deal with. Her coronary heart was weak, and he or she felt like her physique was starting to fail. However she instructed me that after she was comfy sufficient to share her personal story within the PeacEdu classes—to have a look at Karenzi and the opposite Hutu sitting alongside him and inform them about all that they had taken away from her—she began to really feel lighter and stronger. As she saved going to classes, she stated, her psychological and bodily well being started to enhance. She now not wished to die. She had an opportunity to reside once more.

Uwineza was 18 when the genocide started, and he or she was raped a number of instances by Hutu troopers. She contracted HIV from the assaults. Like Muhongayire, Uwineza was reluctant to hitch Rutikanga’s initiative, however when she realized that different girls who had misplaced their households and survived sexual violence have been collaborating, she determined to attempt it. Over time, alongside the opposite survivors, she started to expertise a shift. “I used to be capable of get well,” she stated, holding her thumb and index finger collectively and slowly pulling them aside, “slightly bit.”

Karenzi stated that he’d needed to be taught to put aside his personal guilt. It was not straightforward, he stated, however it was the one option to reveal to survivors that he was not motivated by egocentric causes, that he actually wished to assist them discover closure.

The outcomes modified the realities of each day life within the village. “After I really feel like I wish to go to her home,” Karenzi stated, nodding towards Muhongayire, “I’m free to go there, and vice versa. We have now constructed a really deep belief, and we reside collectively as a neighborhood.” Muhongayire leaned over and stated one thing in Karenzi’s ear whereas putting her hand on his shoulder. They each laughed.

Dialogue teams like these are nonetheless uncommon in Rwanda. In different villages the place Hutu and Tutsi reside collectively, Muhongayire stated, folks could act politely in public, however they don’t seem to be totally healed. Small interpersonal conflicts deliver out deep-seated concern and prejudice. “Inside these Hutu, they’ve a sense: The Tutsi are nonetheless unhealthy. And on the opposite aspect, the survivors additionally really feel the identical method towards the Hutu,” Karenzi stated.

I requested the group if, 30 years in the past, within the fast aftermath of the genocide, they might have ever conceived that they might sit collectively like this in the future. All of them checked out each other and shook their heads, smiling. “We might have by no means imagined it,” Muhongayire stated.

Twenty miles outdoors Kigali, at a church in Nyamata that’s now a memorial website, the garments that have been worn by hundreds of victims are laid throughout dozens of wood pews. The piles are so excessive that initially look, I believed that they have been protecting our bodies. However they have been solely garments. A white sweater with a single pink flower on the collar, a yellow costume with blue polka dots, a small pair of denims stuffed with holes from shrapnel—a kaleidoscope of muted colours.

The information on the website, a lady named Rachel, took me across the church turned memorial and instructed me her story. Each of her dad and mom have been killed within the genocide, as have been her eight siblings. She discovered refuge with a household who took her throughout the border to what was then Zaire. After the killing ended, she returned to Rwanda, this time alone.

Rachel has no images of her household, as a result of the militia set them on fireplace. She nonetheless remembers their faces, however they’ve develop into blurrier. Now, when she tries to recall them, she doesn’t know what’s actual and what she has conjured in her creativeness.

“After the genocide, I felt offended,” she stated. “However these days, no. As a result of should you refuse to forgive somebody, you might have a sort of burden, and it is extremely troublesome to maneuver ahead.”

I thought of slightly woman’s costume I noticed within the church, with pink roses embroidered alongside its sleeves and blood stains streaking throughout its hem. “So forgiving shouldn’t be one thing you probably did for them, as a lot as one thing you probably did for your self?” I requested.

“Sure,” Rachel stated. “For cover.”

This, in so some ways, is the story of Rwanda 30 years later: a narrative of safety. A rustic trying to guard itself from one other genocide, typically by way of deliberate forgetting. On the identical time, memorials defending the bones and our bodies of those that have been killed in an try and make forgetting unattainable. Perpetrators, some who’ve tried to guard themselves from jail and a few who’ve tried to guard themselves from the poison of guilt that threatens to corrode their conscience. Survivors defending the reminiscences of their family members, but additionally their very own stability. The contradictions are innumerable.

As survivor after survivor instructed me, 30 years shouldn’t be that way back. The scars are nonetheless on the land, and nonetheless on their our bodies. It’s unattainable to really overlook. It’s a resolution to forgive. It’s a fixed wrestle to maneuver on.

This text seems within the November 2024 print version with the headline “Is Forgiveness Doable?”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-best-denim-deals-for-fall-tout-6a04c0c94da0408089b2bac22f1cebe8.jpg)