This text was featured within the One Story to Learn At present e-newsletter. Join it right here.

The obsession that may overtake Craig Unger’s life, get him labeled a member of the “tinfoil-hat brigade,” and practically destroy his profession as an investigative reporter took root on an April morning in 1991. Scanning The New York Instances and ingesting his espresso, he came across an op-ed detailing a treasonous plot that had sabotaged Jimmy Carter’s reelection efforts a decade earlier—a plot that may turn into identified, considerably sarcastically, because the October shock.

Gary Sick, a former Iran specialist on the Nationwide Safety Council, was alleging that in the course of the 1980 presidential marketing campaign, whereas greater than 50 People had been being held hostage in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s crew made a backroom arms take care of the brand new Islamic Republic to delay the hostages’ launch till after the election. Carter, bedeviled by the worldwide fiasco, can be denied the narrative he wanted to save lots of his sinking possibilities—an October shock, that’s—and Reagan may announce the People’ freedom simply after he was sworn in (which he went on to do).

This story was “actually unimaginable,” Unger writes in his new e-book, Den of Spies—a criminal offense of the very best order. He was hooked.

Talking with me in regards to the October shock from a leather-based sales space at a Greenwich Village tavern greater than three a long time later, Unger, now 75, lit up. Uncovering precisely how Republican operatives had improbably and secretly labored out an settlement with Ayatollah Khomeini would give him an opportunity to be Woodward and Bernstein, or Seymour Hersh—journalistic heroes whose crusading investigations he revered. “For anybody who had missed out on Watergate, the October Shock appeared to supply one other shot,” he writes in Den of Spies. However it might not be Unger’s Watergate. It could be his undoing. Inside a yr, the story was downgraded to a hoax and Unger was each out of a job at Newsweek and being sued for $10 million. He had turn into, he writes, “poisonous.”

Now, although, on the energy of newer and extra credible proof, he’s returning to the story. Den of Spies is not only a summation of his years of regular analysis into the plot, and never even only a play for redemption; it’s a referendum of kinds on a mode of journalism that after dominated the day.

Unger is what anybody would name an old-school reporter. His instincts had been fashioned in the course of the Watergate period, when the general public’s reflexive belief in authorities was excessive (someplace close to 70 p.c earlier than Richard Nixon took workplace, versus about 20 p.c at present) and journalists started fashioning themselves as adversaries with the presumption that the worst abuses of energy had been occurring behind closed doorways. Their function was to interrupt People’ credulity—they usually did. After I met Unger in mid-September, a second obvious try on Donald Trump’s life had simply occurred. I requested him for his first thought. “Cui bono?” he stated. “Who advantages from it?” He wasn’t saying it had been a false-flag operation. However he positively began from the premise that it may need been.

That is how Unger thinks. His earlier two books tried to cement the concept Donald Trump is an asset of Vladimir Putin. Unger’s modus operandi is to level to many various dots after which marvel at how they could join, even when he can’t join them himself or when these dots are being served up by deeply unreliable sources, akin to a former KGB agent. Suspicion is what issues. He traffics unsure. One unfavorable assessment of his e-book American Kompromat in The Guardian described it as “dozens and dozens of untamed tales and salacious accusations, nearly all ‘too good to verify,’ within the parlance of old-time journalists.”

With regards to the October shock, Unger couldn’t hand over on it, even after it quickly moved from information to obvious pretend information. A buddy referred to as the story his “white whale” (“I didn’t must be reminded that issues had ended badly for Captain Ahab,” Unger writes). With none publication to assist his continued pursuit of the story, he traveled to Paris and Tehran on his personal to interview sources, made his manner via hundreds of pages of paperwork and gross sales receipts, combed via all of it yr after yr. His e-book comprises all of this proof, revealed throughout one other consequential October—and touchdown, as a kind of private reward, on Carter’s one hundredth birthday.

However the world during which Unger is now laying out his proof may be very totally different from the America of 1980, and even of 1991, when his fixation started. Belief in leaders has eroded so utterly that nobody is moved anymore by the revelations of secrets and techniques, lies, or treachery—if you wish to hear about stolen elections, simply tune in to any Trump rally. Definitive proof will now should compete with crazy conspiracy theories. That is unlucky, as a result of the once-debunked October shock has shifted over the identical a long time into the realm of excessive plausibility (although nothing near agreed-upon historical past). And Unger and some different reporters of his era are accountable. They suppose that what really occurred nonetheless issues.

“I don’t prefer to be flawed,” Unger informed me, evident via tortoiseshell glasses. “And worse, I don’t prefer to be referred to as flawed after I’m proper.”

The alleged linchpin of the October shock was William Casey, Reagan’s marketing campaign supervisor via most of 1980. Casey was the pinnacle of secret intelligence for Europe within the Workplace of Strategic Providers, the precursor to the CIA, throughout World Struggle II, and for the remainder of his life maintained a broad community of contacts among the many spies and dodgy arms sellers of the world. He was a furtive, mumbly man; a Manichaean thinker; a Chilly Warrior; and, as Unger put it to me, a “dazzlingly good spy.” Casey additionally appeared to have few scruples about doing what was wanted to win. He was accused of getting obtained Carter’s debate briefing papers in the course of the 1980 marketing campaign. And as soon as the election was over, Casey was made director of the CIA.

A lot of Unger’s e-book focuses on Casey and the connections and motives that may place him on the heart of such a plot, one that may contain breaking an embargo to illegally provide Iran with much-needed spare components and weapons and utilizing Israel as a conduit to take action (a surprising collaboration to contemplate at present).

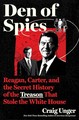

After Sick’s 1991 op-ed, each main information publication sought to observe up and examine. Many of the reporting targeted on whether or not Casey was current at conferences in Madrid on the finish of July 1980, when the plan was supposedly hatched. Infinite trivialities surrounded this query. Unger confirmed me a replica of an attendance chart from a convention in London across the finish of July, at which Casey was a participant. For the 2 days he was supposedly in Madrid for the conferences, a few of the verify marks on the chart indicating his presence in London are in mild pencil, not in pen, that means that he was anticipated however presumably by no means confirmed; did he sneak off to Spain? “Anybody can see this, proper?” Unger stated, squinting on the chart.

The items of this puzzle had been that tiny. Or they concerned shady characters who stated they had been on the Madrid conferences or their follow-ups and will attest to the plotting—individuals such because the brothers Cyrus and Jamshid Hashemi, Iranian businessmen who had been appearing, Unger alleges, as double brokers, pretending to barter the hostage launch with Carter whereas working with Casey to stall it for Reagan’s profit.

Unger, who had been a contract investigative reporter, was employed by Newsweek, shortly after Esquire revealed his first article on the October shock, to affix a crew devoted to monitoring down the plot. Like Woodward and Bernstein on Watergate, Unger imagined the crew would do a sequence of tales main, finally, all the way in which to the White Home. One model of the speculation even positioned George H. W. Bush, who in 1991 was starting a reelection marketing campaign, in Paris for the ultimate planning conferences with the Iranians.

And as with Watergate and different conspiracy investigations of assorted credibility—whether or not the cigarette business’s cover-ups or Iraq’s purported weapons of mass destruction—this one relied on a rogues’ gallery of sources. Unger made contact with Ari Ben-Menashe, an arms seller who claimed to be an intelligence asset for the Israeli Navy Intelligence Directorate. Ben-Menashe gave Unger particulars in regards to the deal and described Casey’s participation. Unger knew that Ben-Menashe was not precisely to be trusted—most Israeli intelligence officers dismissed him as a low-level translator—however Unger thought-about it well worth the threat. “The reality is, individuals who know most about crimes are criminals,” he informed me. “Individuals who know most about espionage are spies. And what you wish to do is hear them out and corroborate.” When he tried to do this, Unger stated, he was “eviscerated.”

Newsweek was not thinking about an incremental Watergate-like construct. As a substitute of Unger’s scoops, they revealed an article about how Ben-Menashe was a liar who had helped invent the story of the October shock. Different publications adopted. Unger had no time and no outlet to make his case, and he seemed like he’d been taken for a journey. These characterizations, he stated, “carried the day when it comes to making a essential mass that overwhelmed any knowledge we may floor.”

Unger was quickly out at Newsweek. Then he and Esquire had been sued for libel by Robert “Bud” McFarlane, Reagan’s nationwide safety adviser (the case was thrown out, and McFarlane misplaced his subsequent enchantment). Two congressional investigations trying into the plot had been launched within the early Nineteen Nineties; the Home produced a virtually 1,000-page report. Each inquiries concluded that no proof of a conspiracy existed. In accordance to the chair of the Home activity power, the entire story was the product of sources who had been “both wholesale fabricators or had been impeached by documentary proof.”

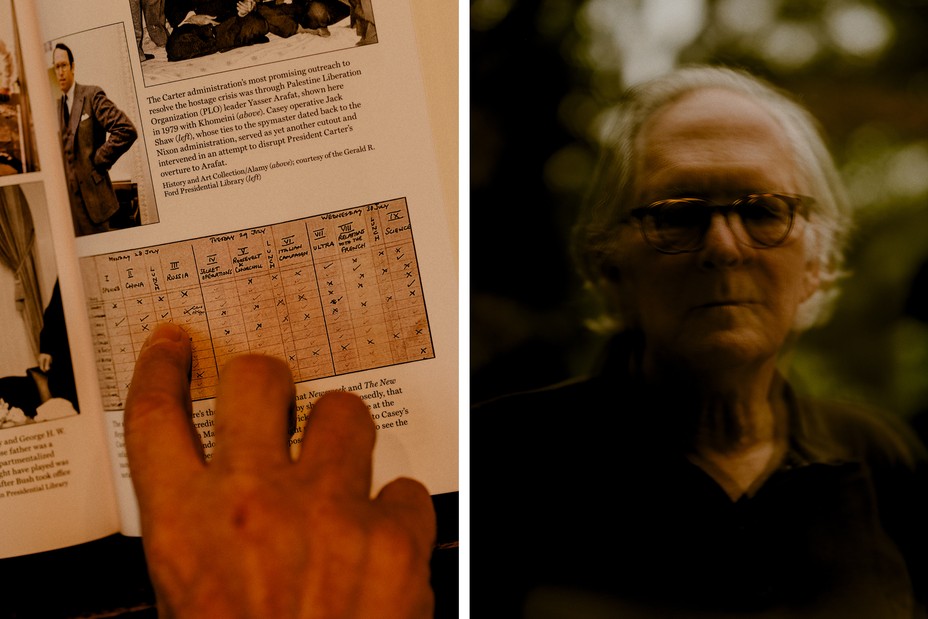

There was no query that when you pursued this, you had been completed,” Unger informed me. He tried to rebuild his profession, finally turning into the editor of Boston journal after which transferring again into freelance journalism. He wasn’t precisely the Ahab of the October shock; that doubtful honor belongs to Robert Parry, one other old-school kind who modeled himself on I. F. Stone, the paragon of impartial journalists. It was Parry who saved discovering extra clues, together with, in 2011, a White Home memo that definitively put Casey in Madrid for the July 1980 conferences. Parry died in 2018, abandoning all of his collected recordsdata, together with 23 gigabytes of paperwork. Unger used this materials to reopen his personal investigation.

Within the years since that first op-ed was revealed, quite a lot of different testimony and proof had helped bolster the October-surprise idea, a few of it from extra dependable sources—notably Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, the president of Iran in 1980, who insisted to anybody who would pay attention that he had been conscious of the plot. Unger went to satisfy with Bani-Sadr at his residence in Versailles, and traveled to Iran in 2014 to see if he may decide up any leads. Among the many new materials within the e-book, Unger reveals data he uncovered that seem to doc shipments of navy tools from Israel to Iran across the time of the November 1980 election.

And simply final yr, The New York Instances revealed a bombshell report during which Ben Barnes, a outstanding Texas politician, revealed a secret he had been conserving for practically 43 years: In 1980, he traveled all through the Center East with John Connally, the previous Texas governor, seemingly on the behest of Casey to ask Arab leaders to influence Iran to delay the hostage launch. Barnes stated he needed so as to add to the file whereas Carter was nonetheless alive. “Historical past must know that this occurred,” Barnes informed the Instances.

After this story, The New Republic ran an essay co-authored by Sick, the previous Nationwide Safety Council official; Stuart Eizenstat, Carter’s chief domestic-policy adviser; and two outstanding Carter biographers, Kai Chicken and Jonathan Alter. Below the headline “It’s All however Settled,” they wrote that they now “consider that it’s time to maneuver previous conspiracy theories to laborious historic conclusions in regards to the so-called October Shock.” Like Unger, that they had little doubt that Casey “ran a multipronged covert operation to govern the 1980 presidential election.”

The percentages that Unger will get a renewed listening to for the October shock—vindicating himself and possibly Carter too—are low. The newest bizarro episode within the present election may clarify why. As anybody following alongside will recall, the vice-presidential candidate J. D. Vance, searching for to stoke fears about immigrants, helped unfold a rumor that Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, had been consuming residents’ cats and canines. This was not true—and he knew it. “If I’ve to create tales in order that the American media really pays consideration to the struggling of the American individuals, then that’s what I’m going to do,” he just lately informed CNN.

Unger desires to unmask politicians and reveal the reality. However we now reside in a rustic the place politicians appear to brazenly brag about mendacity, and sufficient individuals despise the media a lot that they’re keen to consider these lies anyway. We have now an epistemic drawback that no Woodward or Bernstein may resolve. Detailing a virtually half-century-old conspiracy idea, even with Unger’s mass of proof—the receipts, a videotaped interview with Jamshid Hashemi, these little pencil verify marks on an previous attendance chart—would learn like previous information to 1 half of the nation and partisan revisionism to the opposite half.

Reporters used to have the ability to change the “nationwide dialog,” Unger informed me. That’s what he hoped to do, unattainable because it appears even to him. As soon as upon a time, the massive newspapers and tv networks had, Unger stated, “sufficient authority {that a} large story would actually simply land large and alter the dialog, and that the organs of presidency would immediately click on into motion to reply with congressional investigations. It’s so laborious to get that completed.”

I puzzled, although, in my discussions with Unger, whether or not reporters like him bore a few of the accountability—whether or not the type of skepticism and distrust that marked his era of journalists had helped create our post-truth actuality. There have been moments when he slipped from crusading reality teller to one thing nearer to a conspiracy theorist keen to consider essentially the most outlandish speculations. Within the e-book, for instance, with little or no proof, he entertains the concept rogue spies seeking to undermine Carter sabotaged the helicopters utilized in a failed hostage-rescue mission in April 1980, which ended with eight troopers dying in a crash. I requested Unger whether or not he actually believed this. “Nicely, I feel it’s a risk,” he informed me.

It was simpler to sympathize with Unger—to see the real idealism behind the swagger—when he defined why he couldn’t ever let go of the speculation that had so hobbled his profession.

He grew up in Dallas; his father was an endocrinologist and his mom owned the largest impartial bookstore within the metropolis. Unger informed me a couple of go to he took to the Dachau focus camp when he was 14, in 1963. This was as a substitute of a bar mitzvah. Whereas there, he noticed Germans atoning for his or her nationwide sins, not even 20 years after the tip of the warfare, and it stayed with him, that sincere reckoning with the previous. He informed me it made him consider his metropolis’s personal Lee Park, named after the Accomplice normal and defender of slavery, and the way shameful it was that so lengthy after the tip of the Civil Struggle, Lee’s identify was unapologetically honored.

“When my colleagues and I first took on the October Shock greater than thirty years in the past, we turned actors in a case research of America’s denial of its darkish historical past, its refusal to simply accept the ugly reality,” Unger writes in his e-book. After Unger informed me the story about his childhood and Lee Park, I seemed up the inexperienced area and noticed that it had been renamed Turtle Creek Park in 2019. Ugly truths, even in America, do often get acknowledged—however it could possibly take longer than one journalist’s lifetime for that to occur.

Whenever you purchase a e-book utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.