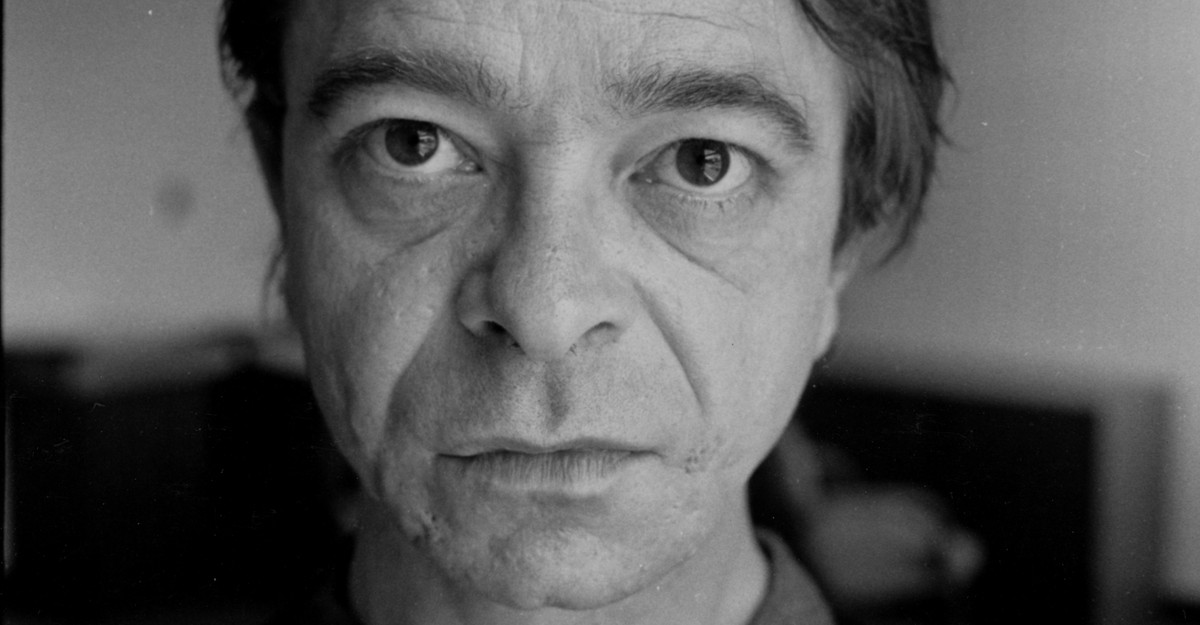

The author Gary Indiana, who died final week on the age of 74, wrote about his obsessions with the calculated grace of a person who discovered them barely embarrassing. He was a stylist of exceptional erudition, and possessed a startling vary; his essays, criticism, performs, movies, and fiction spanned seemingly limitless subjects, amongst them French Disneyland, Cuban prisons, the journalist Renata Adler, the sculptor Richard Serra, true-crime tales, the Boston Marathon bombings, and numerous males whose magnificence slayed him. For the previous a number of many years, he lived in a sixth-floor East Village walk-up cramped with 1000’s of volumes of literature. In Horse Loopy, Indiana’s first and greatest novel, his unnamed narrator invitations a potential boyfriend to his equally cluttered condominium and feels ashamed—not of its mess, precisely, however of the sheer variety of books on his cabinets. “I suppose that is my life,” he says, after longing “for a rubbish dumpster sufficiently big to swallow the whole previous.”

Born Gary Hoisington in Fifties New Hampshire, Indiana moved to the San Francisco Bay Space within the aftermath of the famed Summer season of Love and spent the remainder of his life unromantically hungover from the interval. The bohemian inventive milieu the place he got here of age was shifting towards the pop, the conceptual, and the camp, however Indiana was each suspicious of the longer term and unwilling to be within the thrall of the standard. He participated within the debauched, stoned zeitgeist but wrote about intercourse with out triumph or tenderness—his lovers have been scorned, dissatisfied. After shifting to New York Metropolis in 1978, he grew to become one of many defining countercultural writers of the ’80s, a decade he skewered; his tenure as Village Voice’s artwork critic was notable extra for what he despised than for what he favored. But a lot of what he lampooned all through his profession obsessed him—beautiful younger homosexual males, weird drug addicts, the thorny legacy of the ’60s, the downtown Manhattan scene he all however embodied despite the fact that he refused to be affiliated with it. He saved the tradition of his time near his chest, as a result of what was in vogue fueled his indignation.

Horse Loopy is a very caustic expertise. The novel’s very Indiana-ish narrator has lately landed a fascinating job as a cultural critic at an influential journal—a second of recognition that terrifies and distresses him. He has a bit of cash, however he finds cash disgusting; he can write about something he needs, however this freedom seems like a jail. “The much less free I’m, the freer I look like,” he tells the reader, in one of many guide’s many takedowns of the inventive life. One may think that the 35-year-old has extra tender emotions towards Gregory Burgess, a 27-year-old former heroin addict of “extravagant comeliness,” to whom the narrator writes an “old style” 20-page single-spaced letter professing his need.

But Horse Loopy is likely one of the greatest American novels about obsession partially as a result of the narrator largely dislikes Gregory, subjecting this object of lust to the identical derisive inside voice that feedback on nearly each different side of his life. His pristine exterior however, Gregory personifies the very components that make the guide’s protagonist wish to retch: He’s an ascendant photographer whose fussy, costly prints are sourced from pornography magazines (to which he expresses a moralistic opposition that exasperates the narrator). He’s extraordinarily articulate, but a lot of what he says is fatuous and clichéd, knowledgeable by undigested pop psychology picked up seemingly via the osmosis of youth. The narrator detests Gregory’s music tastes, his inventive opinions, and, after ample publicity, his allure. He admits to having fun with Gregory’s persona solely throughout a buying expedition at a Salvation Military, the place the youthful man picks out grotesque clothes after which reveals that he selected them exactly for his or her hideousness—he needs to offend the sensibilities of the restaurant the place he waits tables. Carried away by a uncommon gust of sentimentality, the enamored narrator brushes some freshly fallen snow from his beloved’s hair.

Love, in Horse Loopy, is transactional, one-sided, unconsummated, and merciless; it pushes Indiana’s fictional stand-in out of dreamy solitude and into the savage current. The unbearable sides of Gregory’s persona are reflections of Indiana’s metropolis and period. Horse Loopy got here out in 1989, on the shut of a decade that noticed New York wrecked by each AIDS and drug epidemics. Gregory refuses to have intercourse with the narrator partially due to HIV fears, despite the fact that he could also be sleeping with different individuals. He’s duplicitous about cash, and the protagonist worries that he could also be supporting a drug behavior. Indiana holds out the chance that most of the narrator’s suspicions are projections of his personal habits—he, too, has a penchant for mendacity to his pals, borrowing money from them, after which by no means paying them again. He drinks continually and grows depending on pace. His former lovers are dying of AIDS, and he fixates on the virus’s incubation interval to determine whether or not he’ll additionally get sick.

Indiana understood that romantic obsession is timeless, a perpetual coil that revolves round itself solely to be severed as a result of its ostensible focus is a person in a specific time and place. Each element of Gregory’s life appears dredged from a satirical model of New York Metropolis, after the so-called homosexual most cancers was recognized and earlier than Rudy Giuliani grew to become mayor. The restaurant the place Gregory works is owned by a coke-addled Frenchman named Philippe who wields cleavers to threaten his staff—a humorous and well-deployed stereotype of the epicurean figures who cropped up as Manhattan’s meals scene exploded through the ’80s. Gregory’s pricey photographic apply echoes the monumental Cibachrome prints of the then-buzzy artist Jeff Wall, and extra usually the cash that flowed into galleries all through the last decade. His apparently ham-handed embrace of identification politics (“I’ve no proper to make use of photos of girls,” he says about his work) displays an age when such issues have been starting to realize prominence in artwork discourse. Gregory’s judgmental views on intercourse comically echo the tradition wars raging in america when Horse Loopy was revealed. If the novel’s narrator, and maybe Indiana himself, discovered these items alternately tiresome and foreboding, additionally they drew him out of his life and his partitions of books, providing the imprecise promise that he could possibly be a lover and never an observer—which is to say, that he could possibly be much less like himself.

However Horse Loopy, like a lot of Indiana’s output, avoids a thoroughgoing cynicism even because it disregards affection as “the mortal sickness of lonely individuals.” Indiana diminished ideas similar to love and hope not as a result of his life or his work lacked them, however as a result of he didn’t need these nebulous formulations for use as Band-Aids on continual societal issues and signs of the human situation. In Horse Loopy, his implacable skepticism forces the reader to think about the alienating results of an period characterised by deadly STIs, unrepentant capitalism, bulldozed cultural historical past, and pervasive substance habit. The guide’s real love affair is with what can’t be reclaimed: a world untouched by illness and unspoiled by cash. Indiana’s thought of being truthful was to react precisely the best way his epoch wanted him to. The withering vestiges of avant-garde New York—the writers, critics, artists, filmmakers, and dancers who’ve held on since its peak—really feel rather less important in the present day with out his contempt.