James Earl Jones would say, throughout the various years that he was requested about his position in Star Wars, that he recorded his unique efficiency as Darth Vader in solely a few hours. The voice is so ingrained in our tradition that imagining how little time the precise work took is sort of comical. However a few hours was all that was wanted. The purpose, Jones would say, was to restrict himself to a selected margin of expression. Too a lot, and Darth Vader could be overly humanized. Too little, and audiences would overlook that the person actually was human, as soon as—and miss the tragedy of the arc George Lucas would take many years to flesh out, the trail that introduced Vader from a frightened, susceptible boy to an indomitable intergalactic terror. Due to Jones, every part was there from the beginning.

At the same time as a baby seeing the film for the primary time, I knew to be bowled over by the mismatch between the thundering voice and the meek and (notably) white man that Darth Vader was ultimately revealed to be, as soon as the helmet got here off. Jones’s voice suited the person within the masks: lacquered, expressionless, disembodied, imperturbable. It matched Darth Vader’s imaginative and prescient of energy—not the small human contained inside, however the grandiose projection that this small human wanted us to consider he was. It matched Jones himself: a towering determine, with a voice constructed to echo by the opera halls of our minds, but additionally very a lot a flawed, fiery, mischievous human with a different and broad profession, even when the favored creativeness didn’t all the time seem to understand it.

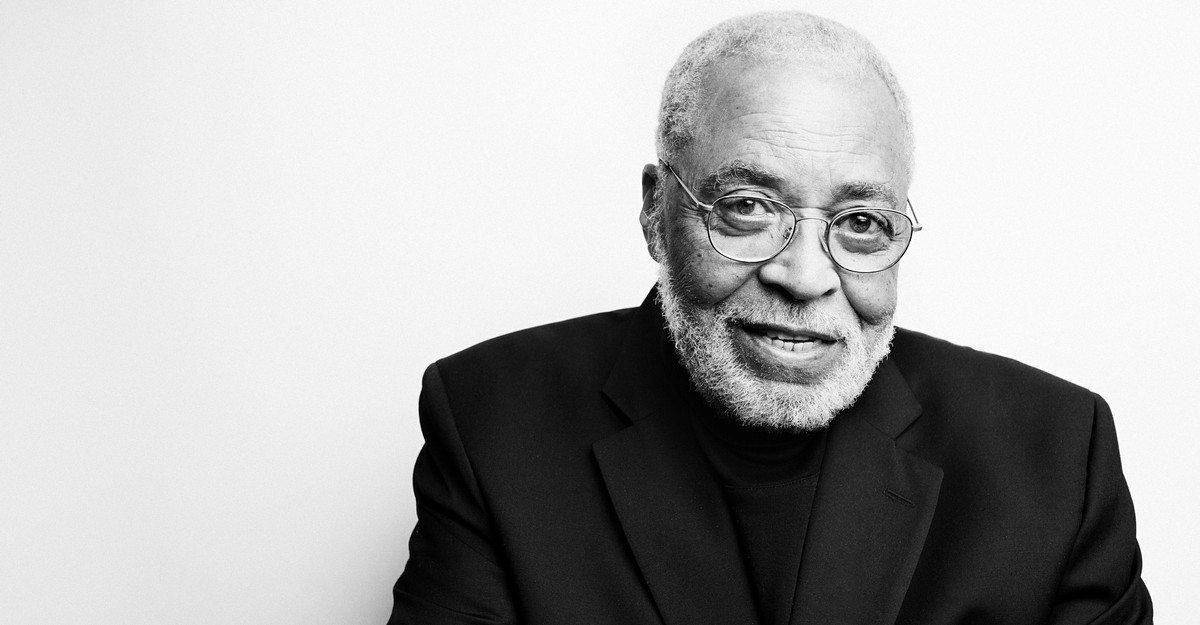

Jones’s demise yesterday, on the age of 93, caps a profession that seemingly knew no bounds—greater than 100 display credit alone, a exceptional truth for any actor, however a very uncommon truth for a Black actor whose profession obtained began onstage within the Fifties and on-screen within the ’60s, with a slight however memorable flip in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove or: How I Discovered to Cease Worrying and Love the Bomb. By the point he landed his full-fledged breakthrough position in Hollywood, enjoying a Jack Johnson–impressed boxer in The Nice White Hope (1970), Jones was already a Tony winner, for enjoying that very same position on Broadway.

But for many people, Jones was, initially, a voice. This was no small feat for a person who usually recounted having gone mute as a baby, after his grandparents uprooted him from Mississippi to Michigan; he started talking once more solely when a high-school instructor inspired him to learn a few of his personal poetry in entrance of the category. He had a foul stutter, but grew to become arguably probably the most recognizable voice on the planet. His was the resonating bass that many individuals heard once they referred to as 411; the voice introducing CNN and promoting Verizon and Dash (“Totes Mcgotes!”); the voice persuading you to seek the advice of the Yellow Pages.

It may be onerous to keep in mind that he was greater than a voice. Final night time, I revisited the 1974 movie Claudine, which stands out, amongst Jones’s display roles, for its reminder that he was not merely a noble patriarch, a la The Sandlot and Area of Desires, or trusted authority determine, as in his brief stint as a detective on TV’s Paris. For a time, Jones appeared to flirt with turning into a intercourse image, enjoying a task that feels extraordinary now given his picture. In Claudine, he starred as Rupert “Roop” Marshall, an attractive rubbish man whom Diahann Carroll, within the titular position as a working mom with six children barely getting by, can’t assist however fall for. That is considerably to her detriment, but additionally very a lot to her pleasure, which the movie noticeably lingers on: lengthy scenes of Claudine and Roop in mattress, smoking after intercourse, speaking throughout intercourse, a lot of their lives enjoying out within the tight confines of his Harlem bed room, an escape from the even tighter digs of Claudine’s crowded, noisy condominium. Jones seduces us simply as he seduces her, with that glint of mischief in his eye, that hop-and-skip pleasure coursing by his physique, a sexual rowdiness and candor that—to make a declare that’s made too usually these days however is definitely true on this case—is never seen in romantic comedies in the present day.

What makes Claudine value watching 50 years later is the way in which Jones’s seductiveness is given room to fester. Our stance on his character is allowed to alter, as Claudine’s troubles with welfare and Roop’s anxieties about Black fatherhood and his value as a breadwinner—actuality, in different phrases—overwhelm their romance. It’s no exaggeration to say that later in Jones’s profession he would solidify into one thing of a nationwide father determine, a presence we may all, throughout a big vary of views and variations, lean on and share. Claudine, with its tortured prescience, appears to see this coming; I’m not your father, his efficiency says.

Jones was typically classed alongside the Sidney Poitiers and Harry Belafontes of Black Hollywood, by brunt of being a “crossover” star within the ’60s and ’70s. He was notable for with the ability to attraction to each Black and white audiences, not solely commercially but additionally as measured by the business’s markers of success: Tonys and Emmys (Jones had a number of of every), profession endurance, and the like. What’s simply as true is that we now have demanded that our mainstream minority stars, notably of Jones’s period, possess a way of responsibility that we anticipate from nearly nobody else. Performers can by no means simply straddle the reality of their very own id and the wants of the broader tradition. Through the years, Poitier was criticized exactly due to the attraction he held for white American audiences, whether or not he intentionally courted that attraction or not.

Jones, whose profession peaked a bit of later and at a much less despairing second in historical past than Poitier’s, fared considerably higher. Watching him in Claudine, or revisiting his Tony-winning flip onstage in Fences, audiences couldn’t miss who he was or what he used his physique—these lengthy limbs and brilliant expressions, his barrel chest—to imply. He was a titan given the profession that he deserved—a profession greater and broader than most actors’. And it’s to his credit score that even this was not large enough.