This text was featured within the One Story to Learn At the moment publication. Join it right here.

On a sunny morning in October 2023, a 90-year-old girl in a blue blazer walked slowly towards the principle courthouse in Shizuoka, a metropolis on the Japanese coast a couple of two-hour drive south of Tokyo. The lady, Hideko Hakamada, led a procession of attorneys and supporters carrying a broad, sky-blue banner, and as they approached the courthouse, a throng of some 300 folks started clapping and chanting encouragement. A cluster of TV-news crews had arrange close by, and Hideko turned to greet them.

As she informed the courtroom later the identical morning, she had come to proper a unsuitable that had been finished in that very constructing 55 years earlier. Hideko Hakamada is the sister of Iwao Hakamada, a former skilled boxer whose lengthy battle for justice has change into one of the vital celebrated authorized causes in Japanese historical past. He was discovered responsible of murdering 4 folks in 1966, in a trial so flawed that it has change into a textbook instance of wrongful conviction.

Hakamada was sentenced to loss of life, and spent the following 5 a long time in a state of debilitating worry. Prisoners in Japan will not be informed when they are going to be executed; they hear each morning for the footsteps that might precede a key turning of their cell door after which a brief stroll to the hanging chamber. No warning is given to their attorneys or members of the family. Hakamada spent longer on loss of life row than anybody else in historical past, incomes a spot in Guinness World Data. He wrote eloquently in regards to the every day psychological torture he endured, and in the long run it drove him mad. His agony modified the lives of many individuals round him, together with one of many unique judges, who grew to become satisfied of his innocence and spent the remainder of his personal life racked with guilt.

Lately, Hakamada, who’s now 88, has change into a logo in Japan not simply of wronged innocence however of what’s often known as hitojichi shiho, or “hostage justice.” Police in Japan have the facility to carry suspects and interrogate them for months with out giving them entry to a lawyer. The objective is to extract a confession, which Japanese prosecutors see because the centerpiece of any profitable legal case. Hakamada was subjected to brutal interrogations for 23 days—lasting as much as 16 hours a day—till he signed a confession (which he recanted quickly afterward).

These routine practices have led to a conviction fee of 99.8 % for circumstances that go to trial. They’ve additionally led to so many accusations of coercion that there’s now a Japanese phrase for the phenomenon—enzai, which means “false accusations resulting in imprisonment.” The system can also be closely weighted towards granting retrials which may give convicted folks a second probability. In Hakamada’s case, it took greater than 50 years for him to obtain one.

The Japanese fixation on acquiring confessions is centuries outdated. As Takashi Takano, a distinguished Tokyo legal professional and a critic of the system, defined to me, it’s rooted in a perception that the state should elicit regret from offenders so as to rehabilitate them and bolster social concord. One in all Takano’s shoppers was Carlos Ghosn, the previous Nissan CEO, who was smuggled from Japan in a musical-equipment field in 2019 after being arrested on expenses of monetary misconduct and interrogated for lots of of hours. The Ghosn case gave the skin world a uncommon glimpse of the facility of Japanese prosecutors.

The info of the Hakamada case have been egregious sufficient to anger even insiders. In 2014, a decide launched Hakamada from jail, granting him a retrial and delivering a stinging rebuke to the police, strongly suggesting that they’d fabricated the proof—a pile of bloodstained clothes—that had helped convict him. In line with the decide, the person who supervised Hakamada’s interrogation was identified amongst attorneys because the “king of torture.” The long-delayed retrial concluded in Could, and Hakamada was lastly acquitted in late September.

At this level, Hakamada could also be past understanding what his exoneration means. He has generally stated issues that counsel he believes he was by no means in jail. He seems to have survived solely by escaping into an imaginary world the place he’s omnipotent—a king, an emperor, even “the almighty God.” (Hakamada embraced Catholicism whereas in jail.) However the prospect of a retrial helped provoke a reform motion led by attorneys, ex-judges, different wrongly convicted folks, and even some Japanese boxers, who see Hakamada as each a determine of heroic struggling and the sufferer of a lingering social prejudice towards their sport. These advocates have been pushing Japanese officers to rewrite the legal guidelines that undergird the apply of hostage justice. A lot of them have drawn inspiration from Hakamada’s personal jail writings, copied and handed round in samizdat kind.

“Conscience is the one voice that protects the lifetime of an harmless man,” he wrote in a journal entry in 1981, when he was nonetheless lucid. “The voice of conscience echoing ever louder and better for so long as the agonizing nights final.”

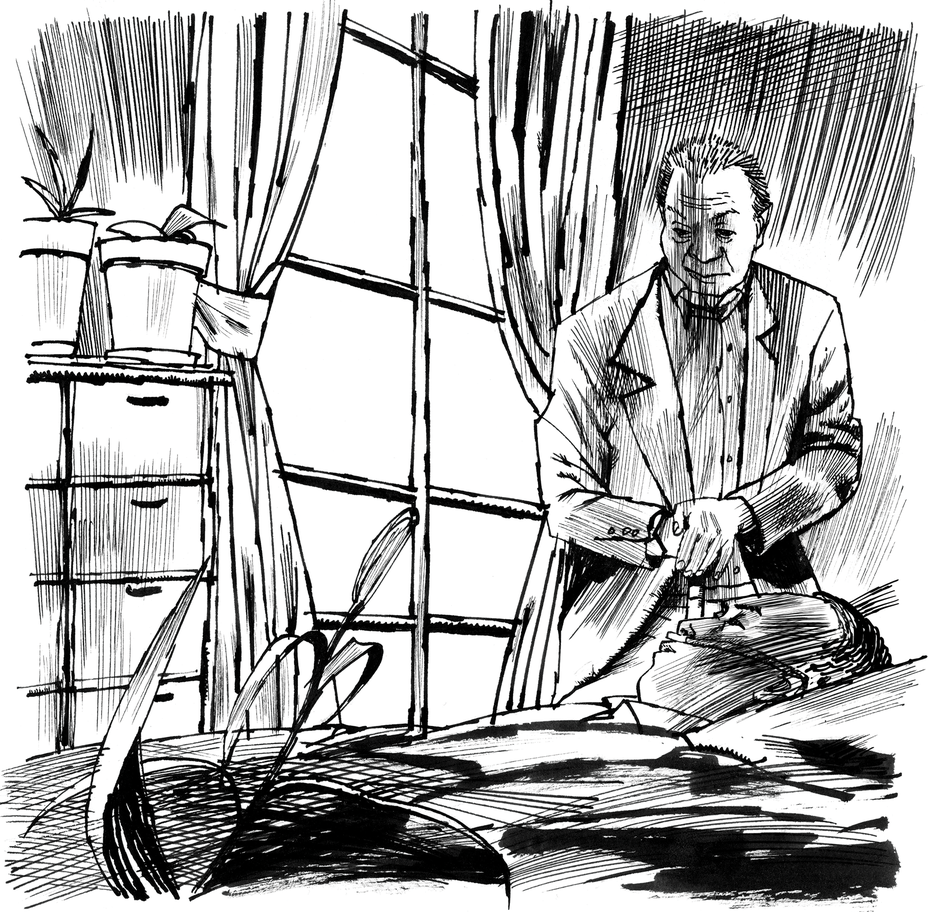

Once I first noticed Iwao Hakamada, he was sitting at a desk within the third-floor residence he shares with Hideko, consuming cooked eel and rice from a bowl. He nonetheless has the small, sturdy body of a featherweight boxer, together with a big, sloping brow and small eyes that give him the look of a sleep-addled bear.

Hideko, who had met me on the door, launched me to her brother. I bowed a greeting, however Hakamada glanced up solely briefly and went again to his eel and rice. The residence was comparatively massive by Japanese requirements, and it struck me that it should have appeared huge when Hakamada was launched from his tiny cell. With Hideko’s encouragement, I stated a couple of phrases about why I used to be there and requested my first query, about why he had change into a boxer.

“As a result of I made a decision I wanted to be sturdy,” he replied. It was a promising begin for a person who was stated to have misplaced contact with actuality. However then he received up shortly and walked away, signaling that the interview was over. Hideko had warned me that her brother was not able to telling a stranger his story.

Nonetheless, the lengthy arc of his incarceration—from passionate self-defense to deepening despair to encroaching madness—is captured in some 5,000 handwritten letters and journal entries that Hakamada produced in jail. In a way, these pages are the place his soul resides, maybe extra so than within the ghostly outdated man who was now sitting in a leather-based armchair within the subsequent room. They have been the true cause I had come.

Hideko received me a cup of tea and started carrying heavy packing containers of Hakamada’s jail letters and journals to the desk, dismissing my efforts to assist. She is small however impressively match for her age, with a routine expression of resilient good humor on her face. The pages are in certain volumes, every one as thick as a bible.

She started leafing by them, displaying me how Hakamada’s handwriting had modified through the years. It begins out wobbly and cartoonish; he had by no means been an excellent scholar, she stated. He was the youngest of six siblings born to a working-class household in a village close to Shizuoka, a quiet boy who liked animals and used to carry house cats and birds and provides them names. Hideko was the second-youngest, by her personal account a tomboy and a loudmouth. “He would imitate what I did,” she stated. He started boxing when he was 19—there was a fitness center close by—and turned skilled on the age of 23, boxing 19 matches in a single yr (a document in Japan). However he determined to retire after an damage, and ultimately received a job at a small miso manufacturing unit not removed from his mother and father’ house. He married an area girl, and the couple had a toddler.

Hideko paused, resting her hand on one of many binders, after which informed me in regards to the night time that modified every little thing: June 30, 1966. A hearth broke out after midnight within the house of the miso manufacturing unit’s director, and after the flames had been put out, investigators found the burned our bodies of the director, his spouse, and two of their kids. That they had all been stabbed to loss of life. The next morning, Hakamada went to his mother and father’ home, the place Hideko was nonetheless dwelling, to speak in regards to the stunning information. In the meantime, the police settled on Hakamada because the most certainly suspect among the many agency’s staff, believing the crime to have been an inside job and apparently seeing his boxing expertise as proof of a capability for violence.

In the course of the 23 days of interrogation in a Shizuoka station home, the police used strategies that have been widespread in Japan when authorities have been attempting to extract a confession: sleep deprivation, threats, beatings. I spoke with two different individuals who had tried to keep up their innocence in related circumstances, and each informed me they’d change into so bodily and emotionally spent that they might have stated or signed virtually something to flee. The confession Hakamada in the end signed is implausible on its face: He admitted to a number of eventualities, all of which appear to have been urged to him by the police. Money had been stolen from the house, however the police have been by no means capable of hint any of it to him.

“Please, God, I’m not the killer,” he wrote in one in all many letters to his mom through the first trial. “I’m screaming it day-after-day, and at some point I hope folks will hear my voice that reaches them by this Shizuoka wind.”

Hakamada couldn’t have identified it, however one of many judges who confronted him as he first entered the courthouse in 1967 was a silent insurgent towards the Japanese approach of justice. At 30, Norimichi Kumamoto was solely a yr youthful than Hakamada, however in most methods their lives couldn’t have been extra completely different. Kumamoto was the eldest of 4 kids, and had been acknowledged as good from an early age. In footage, he’s austerely good-looking, with creased brows and a firmly set mouth. He was well-known at college, one in all his classmates, Akira Kitani, informed me, not only for his mind however for his shows of brazen independence in a tradition that fostered conformity. In the course of the oral a part of the bar examination, Kumamoto argued along with his examiners—a stunning act of insubordination. “He gained the argument, however they failed him” for speaking again, Kitani, who later grew to become a distinguished criminal-court decide, informed me. (Kumamoto went on to earn the highest rating out of 10,000 college students after he was allowed to retake the examination.)

Kumamoto additionally stood out for his curiosity in defendants’ rights. Seiki Ogata, a Japanese journalist who wrote a ebook in regards to the decide, described him as an admirer of Chief Justice Earl Warren, who wrote the U.S. Supreme Court docket’s landmark 1966 Miranda choice requiring that suspects be learn their rights earlier than being interrogated. This was an uncommon perspective in a rustic the place law-enforcement officers have overtly declared their perception that, as one in all them put it, “the suitable to silence is a most cancers.”

Kumamoto seems to have sensed that one thing was unsuitable quickly after Hakamada’s trial started. The prosecutors had no believable proof tying Hakamada to the crime and no believable motive for him to have been concerned within the killings. Years afterward, in keeping with Ogata’s biography, the decide recalled being moved by the boxer’s air of confidence as he asserted his innocence; in contrast to another defendants, Hakamada didn’t appear drawn by an urge to clarify himself. “I slightly really feel that we’re being judged any more,” Kumamoto remembered telling one of many two different judges listening to the case, in keeping with the biography. (Some critical legal trials are dealt with by three judges in Japan.)

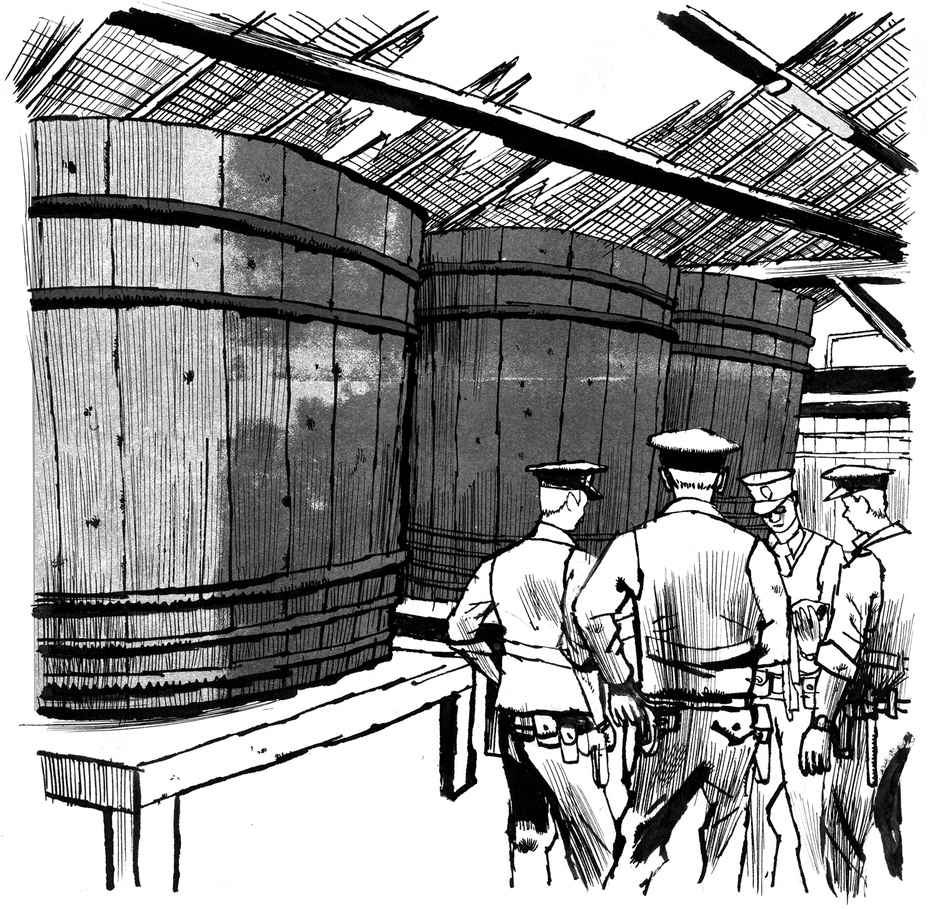

Virtually a yr into the trial—the Japanese justice system tends to take its time—the police claimed to have found a pile of bloody garments on the backside of a miso tank from the manufacturing unit. They declared—although they may not show—that the garments have been Hakamada’s, and that he had hidden them there after the murders.

Decide Kumamoto thought the invention of the brand new proof was far too handy to be actual. The bloodstains have been oddly fresh-looking on garments that have been stated to have been stewing in a miso vat for 14 months, and at trial, the garments can be proven to not match Hakamada. Kumamoto needed to acquit. However in keeping with Ogata, the opposite two judges on the panel, each senior to him, couldn’t imagine that the police or prosecutors had coerced a false confession.

Such religion stays widespread amongst Japanese judges. Some spend a complete profession on the bench with out as soon as delivering an acquittal. “In idea, the prosecutors monitor the police, and the decide screens the prosecutors,” Hiroshi Ichikawa, who spent virtually 13 years as a prosecutor and is now a protection lawyer, informed me. “Nevertheless it doesn’t work like this in any respect. The prosecutor mainly does what the police need, and the judges comply with what the prosecutor needs. So the criminal-justice system is mainly managed by the police.”

Prosecutors are afraid to cross the police, who’ve a lot bigger investigative sources, and infrequently cowl up their errors. Ichikawa startled me by disclosing that he had as soon as, as a prosecutor, personally threatened to kill a suspect if he didn’t confess. He stated his former colleagues principally haven’t modified their methods.

In the summertime of 1968, after weeks of adverse arguments amongst themselves, the three judges within the Hakamada trial held a vote. Kumamoto was alone to find Hakamada not responsible. Then got here a second blow: Because the presiding decide on the panel, he was obliged to put in writing the choice justifying the decision.

Kumamoto reluctantly agreed—to refuse might need ended his profession—however he produced a 350-page doc that could be a poignant document of a tortured conscience. He criticized the investigators’ techniques at size and seemed to be headed for an acquittal. However he then concluded that the defendant was responsible and have to be executed.

One other decide who reviewed Kumamoto’s ruling a few years later informed me that the doc was “very uncommon, to the purpose that it’s irregular … Should you learn the decision, you’ll be able to see that there was not simply disagreement however critical battle of opinion” among the many judges.

Kumamoto refused to signal his personal ruling. He stated he tried to go to Hakamada in jail to apologize, however was not granted permission. “Kumamoto believed the upper courts would overturn the decision, however they didn’t,” Ogata, his biographer, informed me. “Ultimately, he felt actually accountable for what occurred.” That feeling would form the rest of his life.

The 1968 loss of life sentence was a reckoning for everybody within the Hakamada household. Hakamada’s mom, who had been wholesome and robust, fell into despair and died two months after the sentencing. His father died not lengthy afterward. Hakamada was so connected to his mother and father that his siblings saved the information from him for greater than a yr. He continued to put in writing to his mom commonly, and at last the siblings determined they needed to inform him. “I felt an awesome shock, and my complete physique immediately froze,” he wrote in a letter to his brother. “I may do nothing besides have a look at my uncontrollably trembling palms. Feeling the trepidation like darkish waves overtaking my physique, I used to be taken by the urge to curse each being on this world.”

Hideko confirmed me extra of Hakamada’s writings from the years that adopted. He studied arduous in jail, and his kanji characters change into impressively neat and stylish, in completely ordered traces; they appear like the work of a distinct individual. His ideas are extra centered. He talks in regards to the particulars of his case, and generally expounds on the character of freedom and solitude. In a letter from December 1976, he describes feeling aid and inspiration after assembly with college students from a human-rights group: “They imagine I’m harmless. That’s why they assist my trigger. It’s clear that the decision of the excessive courtroom is nonsense … This can be very brutal and unfair, prejudiced, to provide a sentence primarily based on a factual error.”

Hakamada additionally wrote a diary entry addressed to his son, who was 2 and a half years outdated when he was arrested. “Son, I would like you to develop up sincere and courageous,” he wrote.

There isn’t any have to be afraid. If somebody asks how your father is, it is best to reply like this: My father is battling an unfair iron chain … Son, so long as you attempt to do good and survive by studying classes even from this society that is filled with agonies and unkindness, I will return to you in good well being not too far sooner or later. I’ll show to you then that your father by no means killed anybody and that the police realize it greatest, and that the decide is the one who should really feel most sorry.

He appears to have been referring to Decide Kumamoto, although the entry doesn’t say so.

Hakamada’s spouse had divorced him whereas he was in jail. It was there Hakamada realized that the boy had been positioned in an orphanage and that the letters he despatched to his son by no means reached him, Hideko informed me. She stated she has not seen the boy since he was a toddler, and appeared reluctant to speak about him. However her brother generally nonetheless calls out his son’s title: Akira. He can be 60 years outdated in the present day.

Among the letters and meditations Hakamada produced in jail are lyrical. “For some cause, moonlight provides me hope and peace,” he wrote. “Once I suppose that many individuals exterior jail are additionally wanting on the moon, I really feel a way of freedom with different individuals who additionally gaze on the moonlight.”

Though he was on loss of life row, Hakamada remained each hopeful and offended all through the Seventies, certain that his conviction can be overturned on enchantment. At occasions, he wrote about different circumstances of wrongful conviction that he grew to become conscious of by buddies or attorneys. “This scream that I’ve continued to vocalize has not been listened to for the previous 13 years,” he wrote to a boxing commentator. “The dearth of duty of Japan’s justice system is so critical that my pores and skin boils from anger.”

In 1980, Japan’s supreme courtroom confirmed Hakamada’s loss of life sentence. Six months later, the person within the cell subsequent to him, who had change into a pal, was taken out one morning with out warning and hanged. This was a interval of horrible struggling, Hideko informed me. She felt as if her coronary heart would cease each time she heard about an execution on TV. Hakamada’s journal entries and letters are a darkish window into his way of thinking. “Loss of life-row inmates unanimously agree they worry execution very a lot,” he wrote in a letter to his brother. “Actually, it’s not the execution itself they worry: They worry a lot the thoughts that fears execution. This agony, the ache that comes from excessive nervousness, utterly differs from the ache and struggling accompanied by the idea of loss of life.”

A shadow appeared to fall over Hideko’s face as she confirmed me a few of the pages that adopted, from the Nineteen Eighties. “He began to speak about folks sending him alerts by radio waves,” she stated, pointing to the Japanese script. Later, there was discuss of monkeys in his cell with him, and he began sporting luggage on his head and arms to guard himself from dangerous emanations.

Among the many most placing letters are these by which Hakamada appears to be persuading himself that he can discover which means in his struggling. “My want to win innocence is one thing that’s purified and deepened once I settle for loneliness,” he wrote from his cell, a concrete field about seven ft on all sides. “Loneliness is actually very unhappy and painful, however it’s by no means meaningless. When one endures and humbly accepts loneliness, one will certainly understand the deep which means of the trail to victory.”

However because the years handed with no hope of launch—and with sudden execution a every day chance—his thoughts continued to unravel. You may see it in his handwriting, which step by step loses its self-discipline and turns into crazy and uneven once more, as if he have been returning to his childhood self. At occasions, he appeared to hover between insanity and cause inside a single paragraph:

I’m the king of Japan. I need to run flat out, as quick as I can. If I gained my freedom, first I might make this endless dream come true, slicing by the wind with shoulders and hips. Simply pondering of it makes my physique ache. Might I be champion if I simply saved on working? Once I was younger, I used to suppose so. However now I’ve one other reply prepared.

All by the a long time of Hakamada’s imprisonment, Kumamoto was stricken by his function within the case. He resigned his judgeship in disgust lower than a yr after the decision, a stunning choice for somebody who had been seen as a rising star. He discovered work as a lawyer and college lecturer. He additionally grew to become an alcoholic. Two marriages resulted in divorce. He grew estranged from his two daughters, who didn’t perceive the supply of his distress till a few years later, Ogata informed me.

In line with Ogata, Kumamoto as soon as turned himself in to the police, saying he’d dedicated a homicide; he could have been drunk on the time. He appears to have carried Hakamada in every single place, like an accusing ghost. On studying that Hakamada had embraced Catholicism in jail, Kumamoto additionally embraced Catholicism. At one level, he went to a church and requested to admit his sins, as a result of he “needed to really feel nearer” to him, Ogata wrote in his ebook.

Kumamoto seems to have saved his perception in Hakamada’s innocence virtually solely to himself. Japanese judges are anticipated to stay silent about their deliberations, and stoicism about one’s struggling has lengthy been part of Japan’s tradition, maybe particularly for males. However in 2007, whereas dwelling in retirement in southern Japan, Kumamoto started listening to about an rising motion to free Hakamada, which had attracted the eye of some lawmakers. He despatched a notice to one of many activists, providing to assist. Quickly afterward, he appeared on a public panel in regards to the loss of life penalty, the place he mentioned his function within the trial and declared that he believed Hakamada was harmless. He additionally made an apology. “That is the second when one thing that had been caught in my throat and was suffocating me lastly disappeared,” Kumamoto later informed his biographer.

Kumamoto’s feedback have been reported extensively in Japan, partly as a result of he had violated the judicial code of silence. He spoke once more at a session of Japan’s Parliament. The story of his long-repressed guilt and grief captured the general public’s creativeness, and gave rise to a function movie that was launched in 2010, titled Field: The Hakamada Case, in reference to Hakamada’s profession as a fighter. It was not an awesome film—dramatizing a person sitting alone in a cell for nearly 5 a long time is difficult—however the movie did assist draw extra consideration to Hakamada’s state of affairs, each in Japan and past.

Hideko met Kumamoto on the time of his public apology. She informed me she was deeply grateful to him for what he had finished. Her brother was nonetheless locked up, however he was not seen as a monster. “For the reason that information report went out, the world has modified,” she stated. “Even strangers greeted me on the road with a smile.”

Hideko has change into one thing of a public determine in her personal proper. A manga-style graphic novel about her was revealed in 2020. She has the type of life pressure that you simply sense the second you stroll right into a room—her head cocked barely, her eyes gleaming with amusement. She appears proof against remorse, and laughs so usually that it’s straightforward to overlook what she has been by.

She was 35 when Hakamada was convicted of homicide, and it turned her right into a pariah, together with the remainder of the household. The native papers have been stuffed with tales portraying her brother as a demon. She received hate mail from strangers. She grew lonely and depressed, and drank herself to sleep each night time for 3 years, she informed me. However she pulled herself collectively, recognizing that she was her brother’s solely hope. She visited him in jail as usually as she may. She lived alone, working lengthy hours at a authorities workplace after which at an accounting agency. I later realized—from the graphic novel about her life—that she had been briefly married as a younger girl, however she’d by no means talked about that to me. In a way, she was married to her brother’s trigger.

Beginning within the ’90s, with Hideko’s assist, a motion to exonerate Hakamada slowly coalesced. It attracted a various assortment of individuals, and a few pursued the trigger with the type of nerdy obsessiveness attribute of otaku—a Japanese time period for an individual with a consuming passion. One volunteer carried out meticulous experiments with bloody clothes soaked in miso over lengthy intervals to indicate that the prosecution’s claims within the unique trial didn’t maintain up. These experiments have been so rigorous and properly documented that they have been cited by the protection at Hakamada’s retrial a few years later.

Among the many motion’s most passionate supporters have been Japanese boxers. One in all them, a retired bantamweight champion named Shosei Nitta, began accompanying Hideko on her jail visits within the early 2000s. Then he started going alone, as soon as a month. “You couldn’t converse in a traditional approach, besides about boxing,” Nitta informed me once I visited him at his Tokyo boxing fitness center. Nitta cocked his arm, displaying me how he and Hakamada would focus on one of the best approach for a hook punch. Dozens of champion boxers protested in entrance of the supreme courtroom, calling for a retrial.

Among the many many issues the boxers did for Hakamada was attain out to Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, the American prizefighter who was catapulted to fame after Bob Dylan wrote a music about his wrongful homicide conviction. (He served 19 years behind bars earlier than his launch in 1985.) Hakamada himself had written to Carter in 1989, congratulating him on his exoneration and pledging to “comply with in your footsteps.” Twenty years later, a fellow boxer traveled to the USA and introduced again a videotape of Carter providing his assist to Hakamada, who was nonetheless on loss of life row.

“Within the boxing neighborhood, we share this mysterious bond,” Nitta informed me. “However in mainstream society, it’s probably not permitted of. We are attempting to withstand this prejudice, and I feel that’s the reason Hakamada means a lot to us.”

Social prejudice seems to be a standard thread in lots of wrongful-conviction circumstances in Japan. One in all Hakamada’s death-row companions—their cells have been adjoining—was a person named Kazuo Ishikawa, who belongs to the burakumin, the descendants of a feudal caste that was consigned to low-status jobs and nonetheless suffers from discrimination. Ishikawa was convicted of a 1963 homicide on the premise of a coerced confession and a ransom notice, although he was illiterate on the time. He was paroled in 1994, however has all the time maintained his innocence and remains to be, at age 85, attempting to clear his title.

Hideko and her eclectic band of boxers and otaku have helped elevate a broader effort to handle the issues in Japan’s criminal-justice system. Extra persons are coming ahead to contest their verdicts, and several other nonprofits have sprung as much as assist these they imagine to have been wrongly convicted. There’s now an Innocence Undertaking Japan, impressed by the American group shaped in 1992, that makes use of DNA proof to problem convictions. The motion has had some modest victories: Protection attorneys have gained extra discovery rights and have pushed again towards detention orders. Some police interrogations are actually recorded. A “lay decide” initiative, begun in 2009, permits a blended panel of three skilled judges and a mean of six residents to resolve guilt and sentencing in some critical legal circumstances.

There have additionally been setbacks. A lawsuit difficult Japan’s long-standing apply of notifying death-row inmates solely hours earlier than their execution—which possible performed a job in driving Hakamada insane—was dismissed by the Osaka district courtroom in April.

Change of any form comes slowly in Japan, the place those that query authority usually tend to be slapped than rewarded. Most individuals appear to have deep confidence within the justice system, and they don’t seem to be solely unsuitable: Japan incarcerates far fewer folks per capita than the USA, partly as a result of prosecutors are cautious about urgent expenses for much less critical crimes. Sentences are typically comparatively gentle, particularly for many who admit their guilt and specific regret. Prosecutors imagine they’ve a duty to assist offenders return to a helpful life.

However they bridle on the notion that justice will be arrived at by a messy authorized tussle, as in American courtrooms. In Japan, the authorized system behaves extra like some archaic deity: form to those that settle for its judgments, and cruel to those that don’t.

In 2014, after his authorized staff had spent greater than 30 years pleading for a retrial, Hakamada was lastly granted one by a district courtroom. Hideko was then 81 years outdated and retired. She went to the jail to provide her brother the excellent news, trailed by a movie crew. As she was leaving, a guard provided her packing containers stuffed with her brother’s belongings. Hakamada then walked into the room and sat down subsequent to her. The decide, it turned out, had ordered Hakamada’s quick launch. Hideko was completely unprepared. They needed to ask for a experience from the movie crew, however Hakamada, who hadn’t been in a automobile in a long time, received movement illness. They ended up spending the night time in a Tokyo resort earlier than heading house to Hamamatsu, town the place Hideko now lives.

Hideko struggled to get her head across the magnitude of what had simply occurred. The decide had not solely launched Hakamada and granted a retrial; he had taken a sledgehammer to the complete case. He asserted that the investigators appeared to have faked the proof. He cited DNA proof, not accessible through the first trial, displaying that the blood on the garments from the miso tank was neither Hakamada’s nor the homicide victims’.

It might need ended there. The decide had made clear that he believed Hakamada was harmless, and his ruling appeared unanswerable. As a substitute, prosecutors appealed his name for a retrial. As Hakamada moved in along with his sister and started readapting to a world he had not inhabited for the reason that mid-Sixties, his case staggered from one false ending to a different. Lastly, in 2023, the Tokyo Excessive Court docket affirmed his proper to a retrial. Prosecutors, who have been extensively anticipated to surrender, declared that they might search his conviction for homicide once more.

There was little logic of their choice. That they had no new proof, and their possibilities of victory have been close to zero. However as Makoto Ibusuki, a professor at Tokyo’s Seijo College and an authority on wrongful convictions, defined to me, Japanese prosecutors are inclined to see their establishment as infallible. There could have been an added spur on this occasion. The prosecutors who introduced the unique case had been accused within the 2014 ruling of utilizing fabricated proof. David Johnson, an skilled on the Japanese authorized system who teaches on the College of Hawaii at Manoa, informed me that their successors could have felt obliged to defend their repute.

The retrial, which started in October 2023, was like a foul case of déjà vu, with the identical displays of bloodstained garments and miso tanks that had been used half a century earlier—although the state quietly withdrew Hakamada’s discredited confession. “The prosecutors simply repeat what has already been stated,” Hideko informed me. “The expressions on their faces stated, Why do we have now to be right here? ”

For all its frustrations, the retrial gave a giant platform to opponents of hostage justice. The motion’s buoyant temper was on show at a memorial service I attended this previous April at a Tokyo assembly corridor. It was held to honor a person who had been exonerated years earlier after serving practically three a long time for homicide. I discovered myself chatting with an 80-year-old man in an ill-fitting brown blazer who stated he had served 20 years in jail for a homicide he didn’t commit. We have been standing by a giant image window, and he identified the headquarters of the Nationwide Police Company throughout the road. He had been tortured in there for weeks on finish, he stated, in a basement room with no home windows and no clocks. “I perceive utterly how an harmless man finally ends up writing a confession,” he stated.

However a lot of the Japanese public doesn’t perceive. The widow of the exonerated man being honored gave a quick however {powerful} speech, throughout which she stated her father hadn’t needed her to marry a person who had been convicted of against the law, as a result of he believed that “the courthouse by no means lies.”

A nonpartisan group of some 200 Parliament members now needs to make it simpler for defendants to obtain a retrial and is making ready to suggest amendments to the legislation. However getting any such measure previous Japan’s {powerful} Justice Ministry is not going to be straightforward. It’s dominated by prosecutors, and has despatched clear indicators that it’s against reform.

When Hakamada received out of jail, Hideko didn’t ask him about his time on the within. “I used to be ready till he spoke,” she informed me. However he by no means has. Sometimes, he refers obliquely to his time there as “coaching,” as if it had been preparation for some otherworldly fight.

He talks about being visited by the spirits of his lifeless buddies, those who have been led away to the execution chamber, the place a jail official stands behind a blue curtain and presses a button that ends an individual’s life. “When he first got here right here, he’d say there have been spirits of the lifeless trapped within the closet,” Hideko informed me. “He’d faucet on it and attempt to launch them.”

Hakamada’s days revolve round a protracted, principally silent, drive that he’s taken on each afternoon, his eyes centered on the passing streets. He believes that evil influences lurk unseen, Hideko informed me, and that he alone can combat them, just like the boxer he as soon as was. “He feels very strongly that he should surveil,” she stated. “He must go throughout Hamamatsu metropolis. To surveil and defend.”

The acquittal that arrived in September was a balm for Hideko and her supporters. Nevertheless it got here too late for one in all them. Decide Kumamoto, the writer of the 1968 choice, was already significantly ailing with most cancers when Hakamada was launched. The 2 males’s lives had been deeply intertwined for many years, however they’d by no means met exterior the courtroom.

In early 2018, Hideko introduced her brother to Kumamoto’s hospital mattress; he was pale and skeletal, an oxygen tube strapped beneath his nostril. He appeared to be on the verge of loss of life, although he would stay for 2 extra years.

The assembly was captured on movie. The 2 guests, wearing heavy winter garments, seem somber and dumbstruck as they gaze down on the stricken man. Her brother didn’t appear to grasp whom he was taking a look at, Hideko informed me. However Kumamoto clearly knew the face of the person he had condemned 50 years earlier.

“Iwao,” the decide stated, in a scratchy whisper. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

This text seems within the December 2024 print version with the headline “A Boxer on Loss of life Row.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-916441264-00cb9b1bc1344a75bbcb0076051a02a1.jpg)