The modern temporary towards Norman Mailer is lengthy and sordid. He was a misogynist, a violent man who extolled violence. In his brawling and chest-thumping, he tried to out-Hemingway Hemingway and have become a parody of Papa—a blowhard narcissist who provoked and offended like he breathed. For all his profuse writing (dozens of books, together with two that received the Pulitzer, in a profession that spanned six many years), what has lasted within the cultural reminiscence is what he did with a penknife one evening in 1960: He stabbed his second spouse and the mom of two of his daughters, Adele Morales, simply barely lacking her coronary heart. (She survived, and died in 2015 at 90 years previous.)

To revive the Tasmanian satan that was Mailer at this historic second, when a lot of the tradition has accurately chosen to downgrade a author who would interact in such violence after which years later nonetheless brazenly fantasize about retaining ladies in cages, calls for two issues: first, that we not flip away from the worst of him, that we run towards even his most deplorable acts and views; and second, that an energetic case be made that there’s nonetheless one thing to realize from understanding how he lived his life and made his artwork.

A brand new documentary about Mailer, directed by Jeff Zimbalist, achieves each of those goals. The title itself captures the balancing act Zimbalist is making an attempt: The right way to Come Alive With Norman Mailer (A Cautionary Story). What warning does a tour of Mailer’s explosive existence counsel? Is it a warning towards being somebody like Norman Mailer, a person who held onto lit matches so long as potential irrespective of how usually he was burned, or is it Mailer’s personal phrases of warning for us in regards to the must be unafraid, to offend freely, a posthumous bannerman within the struggle towards the censoriousness that has swept by the American left and proper? Which is it? And might or not it’s each?

Except we’re going to comb by the previous thousand years or so and excise the work of any artist whose actions or phrases now appear monstrous to us—and to be clear, we must always not do that—a necessity exists to search out methods to productively depict the lives of deeply flawed and even morally repugnant artists. With this movie, Zimbalist has carried out simply that by embracing ambivalence. The documentary opens in medias res, on Mailer’s darkest second, with a information broadcast about him attacking his spouse at a celebration and being dedicated to the psychiatric ward at Bellevue Hospital. Earlier than we’re informed anything in regards to the nice author, we study what he’s able to doing along with his fingers. His personal phrases comply with, a gravelly crunch that accompanies a lot of the movie: “I believe I’m a troublesome man, and I believe I’m a coward. I believe that I’m good, and I believe I’m dumb. I believe that I’m good, and I believe I’m evil.”

Although the movie is structured as a collection of solutions to the title’s query (Mailer’s imagined suggestions for genuine dwelling, resembling “Don’t Be a Good Jewish Boy” and “By no means Let Life Get Too Protected” are used to introduce every part), the story unfolds in an easy chronological fashion. Born in 1923, Mailer grew up in Brooklyn’s middle-class Jewish ghetto of Crown Heights, son of a mom who bragged to the neighbors about his excessive IQ. He decided early on that he can be an amazing author, even debating which entrance in World Warfare II to struggle in based mostly on its potential as a setting for the warfare novel he meant to jot down. This ambition was realized with The Bare and the Useless, his best-selling brick of a ebook that’s nonetheless thought of among the many most visceral depictions of how troopers skilled that warfare. Fame adopted, after which a metamorphosis within the Fifties right into a radical enemy of conformism. He pioneered the New Journalism of the late ’60s and ’70s, producing his most groundbreaking books by putting himself in the course of the period’s political tumult. By the ’80s, he had settled into a protracted lion-in-winter part, writing ebook after ebook, showing on tv, one of many final of a sure number of superstar writer, as famend for his fame as for his creative output.

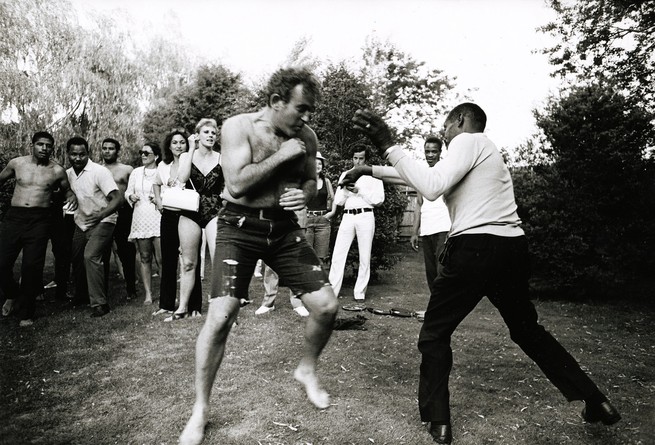

The movie spares Mailer nothing. In addition to the erratic, drunken habits that culminated within the stabbing in 1960, there are the 2 self-indulgent makes an attempt to change into mayor of New York Metropolis. Within the second, in 1969, he and his working mate, Jimmy Breslin, referred to as for town to secede from New York State; their slogan was “The Different Guys Are the Joke.” (I observed one thing distinctly Trumpian within the footage of Mailer on the marketing campaign path—the shamelessness, the bombast, the glee at getting beneath the pores and skin of others—which made me suppose that possibly Mailer’s political ambitions had been simply forward of his time.) Mailer’s Maidstone, a weird work of cinema, can be properly coated. That is the movie he directed by which he performs an inflated model of himself in a captain’s hat and solid his ex-wives to observe as he made out with different younger ladies; it ends, infamously, with the actor Rip Torn smashing a hammer into Mailer’s head in entrance of the writer’s personal terrified kids. Mailer’s thick Popeye physique, his boxer’s gait, his snarl—all of it’s right here.

Zimbalist struggles with how you can course of this ugliness and typically simply throws up his fingers, taking a too-romantic and considerably mystical method to Mailer’s habits, intercutting at sure moments—within the documentary’s most heavy-handed transfer—inventory video of a bull struggle, of a person wrestling a lion, of storm clouds raging. That is meant, I suppose, to sign Mailer’s animalistic urges, an uncontrollable, primal high quality to his nature. However Mailer was not a bull or a lion or a thunderbolt. He was simply, fairly often, an infinite and unrelenting jerk.

Mailer’s volatility and aggressiveness and self-aggrandizement are all freely acknowledged, a lot so {that a} viewer can really chill out and take a contemporary have a look at him, realizing that his important blemishes are nonetheless close by. That is what the movie did for me, anyway, and I discovered that it allowed me to see qualities I might admire, ones that furthermore really feel missing at the moment—Mailer’s mental risk-taking, his ardour for concepts that pushed towards the established order, and his bare inventive ambition; this was a author who strove to be the Muhammad Ali of books. I might respect his embrace of reinvention. Mailer didn’t go in for the trauma plot. One’s origins had been to be transcended. As a way to be robust, you simply wanted to start out appearing robust, and shortly you’ll be robust. All you needed to do was witness his stroll as he made his manner onto Johnny Carson or Dick Cavett—fists balled, arms swinging as if about to punch, barrel chest pushed out like a rooster’s. This was not how Jewish boys with excessive IQs raised in Brooklyn usually walked.

This confidence gave him the nerve to speak about American society in methods, it appears, solely a prophet would possibly dare. Mailer was a grasp of the jeremiad in an period by which quite a few writers—notably Mailer’s nice frenemy, James Baldwin—reached for this register. Mailer’s voice, its supreme knowingness, is woven by the movie: “The scary side of contemporary life is that the chance to have existential expertise—in different phrases, the chance to have experiences the place we don’t know if it’s going to prove properly or badly—is getting an increasing number of restricted on a regular basis. And to the diploma we’re not having an existential life, I imagine we’re extinguishing ourselves.” Mailer checked out America and stated, straight-faced, that what he needed was at least to make “a revolution within the consciousness of our time.”

What American author expresses himself or herself like this anymore? Beginning within the Fifties, Mailer turned a public determine who would poke and prod at the established order. He can be the contrarian—as Homosexual Talese places within the documentary, a determine who was “deliciously reckless, romantically reckless.” Mailer’s elementary level: People wanted to throw up all that was repressed, to confront each other, to struggle it out. Rereading one among his most notorious essays, “The White Negro,” from 1957, I used to be shocked by its racist essentialism—the argument that Black folks have the form of sexual freedom and launch from civilizational hang-ups that white folks ought to emulate (“the identical previous primitivism crap in a brand new bundle,” surmised Ralph Ellison, precisely)—however there may be additionally a muscularity and boldness to the prose itself that’s laborious to show away from. It’s inciting. “If the destiny of twentieth century man is to dwell with demise from adolescence to untimely senescence,” he writes, “why then the one life-giving reply is to simply accept the phrases of demise, to dwell with demise as rapid hazard, to divorce oneself from society, to exist with out roots, to set out on that uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self.”

He genuinely believed in confrontation as redemptive, and the one approach to “come alive.” That is an existence that might be exhausting for many of us, however Mailer appears to have taken it upon himself to change into a sort of sacrificial providing, prepared to place himself ahead to undergo society’s hatred and annoyance if it might convey all the required muck to the floor.

This tendency can be narcissism, and it might overwhelm his artwork, as he sought topics who would possibly mirror the greatness he noticed in himself—see for instance his lackluster books on Marilyn Monroe and Picasso. However narcissism was additionally on the supply of his best literary accomplishments. In The Armies of the Night time, he ingeniously wrote about himself within the third individual, as a “Mailer” who helped lead the cost of anti-war activists on the Pentagon. And in The Executioner’s Track, his best ebook, he explored his personal obsession with violence by telling the true story of Gary Gilmore, a person who had murdered two folks and was sentenced to be executed. Within the documentary, Mailer is seen in candid footage at a kitchen desk in 1979 with two of his sons and his final spouse, Norris Church, explaining the premise of The Executioner’s Track and attempting to have interaction the wide-eyed boys in its themes. “There’s a whole lot of violence on the earth,” he says. “How do you meet violence? Do you meet violence with your individual violence, or do you attempt to keep away from it?” Mailer himself sat again and provided no reply. The narcissism turns into a sort of braveness to place himself on the entrance line of those large questions. As he stated about himself, “I turned a species of fight soldier in life relatively than in warfare.”

By the top, as his hair whitened and his paunch grew, Mailer’s persona softened. He put down his fists and commenced to specific extra humility, even some deep regrets. The documentary consists of most of his kids, and so they converse of him as a constructive drive of their lives, regardless that, as he apparently informed one among his daughters, “I’m a author first and a father second.” The footage of Mailer in his dotage, sitting in an undershirt by the ocean, presents a person struggling to the top to grasp the contradictory forces inside him. However the kids all surrounded him on his deathbed, which maybe says one thing. And their love for him appears real, if sophisticated.

Watching the documentary, I had my very own second of reassessment about simply how nasty Mailer really was. The movie consists of one among my favourite Mailer moments, from a rare 1971 debate in regards to the targets of the then-surging feminist motion. The occasion gathered collectively a who’s who of icons—together with Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer. Mailer had goaded the occasion into being like a pro-wrestling match. It’s unattainable to think about one thing prefer it at the moment, a tradition warfare by which the combatants joyfully interact with each other in individual, not simply tweet from their corners. And Mailer serves himself up because the villain. At one level, the author Cynthia Ozick stands as much as ask a query from the viewers that brings down the home: “Mr. Mailer, in Commercials for Myself, you stated, ‘A superb novelist can do with out every little thing however the remnant of his balls.’ For years and years, I’ve been questioning, Mr. Mailer, once you dip your balls in ink, what coloration ink is it?” It’s an exciting occasion of an idol being smashed. However I’d forgotten what adopted after all of the laughter. Mailer says, humbly, “I’ll cede the spherical to you. I don’t fake that I’ve by no means written an idiotic or silly sentence in my life, and that’s one among them.” An analogous turnaround occurs with Susan Sontag when she asks Mailer to cease utilizing the time period girl author (“It looks as if gallantry to you. It doesn’t really feel proper to us”). Mailer instantly says he’ll stop.

He needed to confront his feminist detractors head-on, and he was prepared to confess his errors, to alter. The violence he inflicted is one thing he regarded ultimately with heartbreak. “What I’ve come to appreciate is that after I stabbed my spouse with a penknife, it modified every little thing in my life,” he stated in an interview many years laters. “It’s the one act I can look again on and remorse for the remainder of my life.” He confronted his personal guilt: “I can’t fake that hadn’t price nothing. It triggered big injury.” He had let down his kids, he stated, and he had let down God. As for Adele Morales, the movie reveals little about what occurred to her after the incident by which she practically misplaced her life, moreover that she turned an alcoholic; one among her daughters stated the stabbing was a “trauma” her mom “by no means received over.”

It’s a disgrace we will’t hear straight from her. One wonders if she would have been capable of see Mailer the way in which the documentary does—as somebody who was deeply flawed however who appeared to redeem himself by an intimate consciousness of these flaws.

When it got here to his inventive life, Mailer needed to constantly make himself weak, which is its personal sort of pathology, stepping as much as the brink of catastrophe as if he loved the fun of potential self-destruction solely to see whether or not he might survive. The boxers who fascinated him had been those that stored getting knocked out and received again up, overcoming humiliation after humiliation. That is how he noticed himself. And in a literary panorama at the moment by which careerism drives the impulses of so many writers , by which authors by no means elevate the stakes for themselves in a critical manner or take large swings which may price them in social capital, Mailer presents an essential provocation. “He embraced the concept to start out considering for ourselves, we must be much less afraid of the response,” says the author Daphne Merkin, one other of the movie’s speaking heads.

Martin Amis as soon as described Mailer as “probably the most turbulent author in America.” And after I heard this phrase, it appeared precisely proper. Turbulence spills your drink and makes you slam your head, nevertheless it additionally jolts you, widens your eyes, straightens your backbone, and forces you to brace your self. I wouldn’t thoughts if we had a couple of writers who might try this.

Once you purchase a ebook utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.