In 1956, the poet Elizabeth Bishop anxious in regards to the imprudence and absurdity of going overseas. “Ought to we’ve stayed at dwelling and considered right here?” she writes in her poem “Questions of Journey.” “Is it proper to be watching strangers in a play / on this strangest of theatres? / What childishness is it that whereas there’s a breath of life / in our our bodies, we’re decided to hurry / to see the solar the opposite approach round?”

A long time later, the phrasing of those questions, and the fretful state of mind behind them, appears to completely sum up a brand new perspective towards worldwide journey: one in all ethical unease. Each summer time, a litany of headlines seems about vacationers behaving badly: individuals carving their names into the Colosseum or posing bare at sacred websites in Bali, for instance. Even the strange enterprise of tourism leaves a lot to be desired: The crowds on the Louvre make seeing the Mona Lisa such a short and unsatisfying expertise; foot site visitors, noise, and trash slowly degrade websites well-known for his or her pure magnificence or historic significance. Within the Canary Islands, the Greek island of Paros, and Oaxaca, Mexico, residents of well-liked locations have protested in opposition to throngs of tourists. For a lot of vacationers, it could actually appear someway fallacious, now, to plunge blithely into one other nation’s tradition and landscapes, subjecting locals to 1’s presence for the sake of leisure, whereas the long-haul flights that make these journeys attainable emit large quantities of greenhouse gases. Bishop’s queries are our personal: Would we be doing the world a favor if we didn’t sally forth so confidently to different nations and simply stayed dwelling?

Amid this quagmire, the journalist Paige McClanahan’s guide, The New Vacationer, is a levelheaded protection of tourism that proposes a genuinely useful framework for desirous about our personal voyages. We vacationers—a label that features everybody who travels overseas for work or enjoyable—take into consideration the observe’s pleasures all fallacious, she says, and low cost its potential. Many people are used to considering of ourselves as easy hedonists once we go on trip, or maybe as financial individuals of the tourism trade. However we’ve largely forgotten “in regards to the energy we maintain as contributors—nevertheless unwitting—to an unlimited and potent social pressure,” McClanahan writes.

The New Vacationer is devoted to fleshing out this chook’s-eye view of tourism as a formidable phenomenon, one which we take part in each time we depart our dwelling nation—and one which we ignore at our peril. Touring the world was as soon as reserved for the very wealthy; now, due to a sequence of current developments—together with the deregulation of the airline trade in 1978 and the launch of Travelocity and Expedia within the ’90s—planning a visit to Iceland and even Antarctica is simpler than ever. The world noticed greater than 1 billion worldwide vacationer arrivals final 12 months, and tourism contributed almost 10 % to international GDP. This monumental site visitors now shapes the world for each good and ailing, as McClanahan demonstrates. Tourism revitalized town of Liverpool and employs almost 1 / 4 of the workforce of the Indian state of Kerala; it’s additionally turning locations comparable to Barcelona’s metropolis heart and Amsterdam’s red-light district into depressing, kitschy vacationer traps and pricing out native residents.

Tourism additionally has the capability to form how vacationers think about different nations. McClanahan dedicates a complete chapter to mushy energy—a authorities’s political potential to affect different states—as a result of, as she factors out, our travels change the place we’re more likely to spend our cash and “which locations we’re inclined to treat with empathy.” Tourism has elevated Iceland, as an example, from a rustic that North Individuals knew little about to a acknowledged participant on the world stage. And Saudi Arabia plans to pour a whole bunch of billions of {dollars} into its tourism trade with a aim of attracting a deliberate 150 million guests a 12 months by 2030. For a nation, particularly one striving to alter its worldwide popularity, the advantages of tourism aren’t merely monetary. “The minute you place your ft on the bottom,” an professional on “nation branding” tells McClanahan, “your notion begins altering for the higher—in ninety % of circumstances.”

Actually, McClanahan took a visit to Saudi Arabia as analysis for this guide. “I used to be scared to go,” she writes, given what she’d learn in regards to the nation’s therapy of each ladies and journalists, “extra scared than I’ve been forward of any journey in current reminiscence.” However she was captivated by her conversations with Fatimah, a tour information who drives the 2 of them round in her silver pickup truck. Over the course of the day, they talk about the rights of Saudi ladies and the assassination of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi. “Her solutions are considerate; many shock me, and I discover myself disagreeing with a number of outright,” McClanahan writes. When McClanahan returned dwelling and printed an interview with Fatimah for The New York Instances, nevertheless, outraged readers excoriated her. “Simply curious—how a lot did MBS pay you to tourism-wash his nation?” one wrote to her in an e mail, referencing Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. “Or was the fee carried out strictly in bonesaws?”

McClanahan likens these commenters to acquaintances who inform her they refuse to go to the U.S. as a result of they’re disgusted by some facet of our nation—American stances on abortion, or immigration, or race. Touring to Saudi Arabia didn’t change her consciousness of the nation’s repression of speech and criminalization of homosexuality. But it surely did give her “a glimpse of the breadth and depth of my ignorance of the place,” and a recognition that the nation must be seen with nuance; along with its regressive insurance policies, she writes, the journey made her acknowledge the complexity of a land that hundreds of thousands of individuals name dwelling.

McClanahan’s anecdote gestures at what we would achieve from tourism—which, she argues, has now turn out to be “humanity’s most necessary technique of dialog throughout cultures.” What bodily touring to a different nation grants you is a way of how strange issues are in most elements of the world. Until you’re limiting your self to probably the most touristy spots, going someplace else plunges you briefly right into a each day cloth of existence the place you will need to navigate comfort shops and prepare schedules and native forex, surrounded by different individuals simply making an attempt to reside their lives—a form of visceral, cheek-by-jowl reminder of our frequent humanity, distinct from the insurance policies of a gaggle’s present ruling physique. Touring, McClanahan suggests, helps individuals extra keenly discern the distinction between a state’s positions and the tradition of its individuals by seeing it with their very own eyes. This firsthand publicity is a significantly better reflection of the reality than flattened, excessive pictures offered by the web and the information. That’s a superb factor, as a result of by sheer numbers, this sort of cross-cultural contact occurs on a a lot bigger scale than every other.

Seeing the broad world extra clearly appears helpful for everybody concerned. However measuring these grand concepts about journey in opposition to its precise results may be tough. How precisely does visiting new locations change you? Can a brief journey, particularly one catered to a international customer, actually give an individual a practical view of life out of the country? McClanahan doesn’t specify what she and Fatimah disagreed or agreed on, or what facets of Saudi Arabia she was unaware of and subsequently discovered on her journey. Within the Instances article, Fatimah’s solutions about what it’s prefer to be a Saudi lady who drives, carrying no head scarf or abaya, are uniformly breezy—“Some individuals may stare as a result of it’s nonetheless form of a brand new factor to see, however they respect my alternative,” she says—and a reader may surprise if, as an envoy for a extra liberal Saudi Arabia, she’s motivated to reply that approach. One might argue that by not urgent additional, McClanahan really avoids Saudi Arabia’s complexity. And this surface-level expertise extends to every kind of journeys: Once I journey, I’ve discovered that the notion that I’m doing one thing good—not only for me, however for the world—can appear impossibly lofty, even self-aggrandizing, amid my stress, exhaustion, and imprecise disgrace. How worthwhile is enlightenment about my very own ignorance in contrast with the concrete hurt of emissions and supporting states with unjust legal guidelines?

And but this rigidity is the crux of the soft-power argument: How individuals really feel about different locations issues, as a result of these opinions form actuality. Dismissing these intangible sentiments raises the danger of falling into the previous entice of seeing journey by a person lens fairly than a social one. What may occur if hundreds of thousands of people have their views of different nations subtly modified? Maybe, McClanahan suggests, we’d achieve the power to exist alongside completely different worldviews with equanimity, with out alarm or intolerance—a vital talent for democracy and peace, and an consequence well worth the downsides of mass tourism.

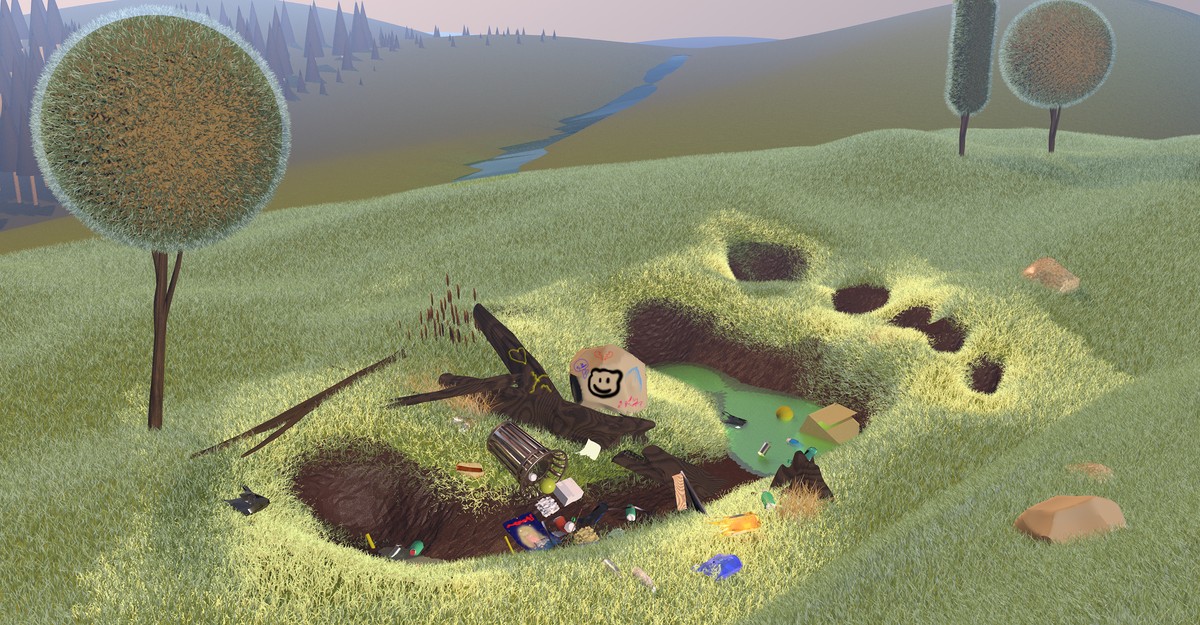

However to encourage this global-citizen state of mind, governments, companies, and vacationers alike have to alter the best way the journey trade works. If we’re to think about tourism a collective phenomenon, then a lot of the burden to enhance it shouldn’t fall on people. “Tourism is an space by which too many governments solely get the memo that they need to listen after an excessive amount of injury has been carried out,” McClanahan writes. (Her guide is filled with examples, just like the poignant picture of tourists trampling pure grass and moss round a preferred canyon in Iceland so badly that the panorama might take 50 to 100 years to get well.) As an alternative, she argues, lawmakers ought to enact rules that assist handle the inflow, and he or she lists concrete steps they will take: setting capability limits, constructing infrastructure to accommodate site visitors, banning short-term leases that drive up costs the world over, and ensuring that a lot of the cash and different advantages move to native residents.

However the social lens additionally means that there are higher and worse methods to be a vacationer. Touring will at all times be private, however we will shift our conduct to acknowledge our position in a broader system, and likewise enhance our possibilities of having a significant expertise. McClanahan sketches out a spectrum with two contrasting varieties on the ends, which she politely (and optimistically) dubs the “previous” and “new” vacationer. The previous vacationer is actually the boorish determine from the headlines—solipsistic, oriented towards the self, somebody who superimposes their fantasies onto a spot after which is outraged when their expectations aren’t met. What units aside the brand new vacationer is a deal with the place they’re visiting. Don’t make it about you, in brief: Make it about the place you are.

Touring effectively, then, entails fundamental acts of bodily courtesy: Don’t litter, don’t cross obstacles meant to guard wildlife, don’t take fragments of seashores or ruins, and customarily don’t be a nuisance. But it surely additionally entails some quantity of analysis and significant desirous about the vacation spot itself. I’ve taken to utilizing my worldwide journeys as crash programs within the historical past of a specific nation, which largely means studying books and spending giant quantities of time at museums and historic websites. However that is simply what I occur to take pleasure in. One might simply as profitably attempt choosing up the language, having conversations with residents about their lives (if they appear involved in speaking to you, in fact), venturing to much less well-known locations, or studying the nation’s newspapers and studying what points individuals care about. The purpose is to speculate one thing of oneself, to attempt to interact with a special place—an effort that strikes me as a extra trustworthy accounting of the simple prices of going overseas. Even Bishop concludes, in “Questions of Journey,” that the endeavor is finally worthwhile. “Certainly,” she writes, “it will have been a pity / to not have seen the timber alongside this highway, / actually exaggerated of their magnificence, / to not have seen them gesturing / like noble pantomimists, robed in pink.”

While you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/selenasocial-2312421d0e3e4888b8a1c0e21ed6be7e.png)