For anybody who teaches at a enterprise college, the weblog put up was unhealthy information. For Juliana Schroeder, it was catastrophic. She noticed the allegations once they first went up, on a Saturday in early summer time 2023. Schroeder teaches administration and psychology at UC Berkeley’s Haas Faculty of Enterprise. One in every of her colleagues—a star professor at Harvard Enterprise Faculty named Francesca Gino—had simply been accused of educational fraud. The authors of the weblog put up, a small workforce of business-school researchers, had discovered discrepancies in 4 of Gino’s printed papers, and so they advised that the scandal was a lot bigger. “We consider that many extra Gino-authored papers include faux knowledge,” the weblog put up mentioned. “Maybe dozens.”

The story was quickly picked up by the mainstream press. Reporters reveled within the irony that Gino, who had made her title as an knowledgeable on the psychology of breaking guidelines, might herself have damaged them. (“Harvard Scholar Who Research Honesty Is Accused of Fabricating Findings,” a New York Occasions headline learn.) Harvard Enterprise Faculty had quietly positioned Gino on administrative go away simply earlier than the weblog put up appeared. The college had performed its personal investigation; its practically 1,300-page inner report, which was made public solely in the midst of associated authorized proceedings, concluded that Gino “dedicated analysis misconduct deliberately, knowingly, or recklessly” within the 4 papers. (Gino has steadfastly denied any wrongdoing.)

Schroeder’s curiosity within the scandal was extra private. Gino was certainly one of her most constant and essential analysis companions. Their names seem collectively on seven peer-reviewed articles, in addition to 26 convention talks. If Gino have been certainly a serial cheat, then all of that shared work—and a big swath of Schroeder’s CV—was now in danger. When a senior tutorial is accused of fraud, the reputations of her sincere, much less established colleagues might get dragged down too. “Simply assume how horrible it’s,” Katy Milkman, one other of Gino’s analysis companions and a tenured professor on the College of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Faculty, informed me. “It may destroy your life.”

To move that off, Schroeder started her personal audit of all of the analysis papers that she’d ever carried out with Gino, searching for out uncooked knowledge from every experiment and trying to rerun the analyses. As that summer time progressed, her efforts grew extra formidable. With the assistance of a number of colleagues, Schroeder pursued a plan to confirm not simply her personal work with Gino, however a significant portion of Gino’s scientific résumé. The group began reaching out to each different researcher who had put their title on certainly one of Gino’s 138 co-authored research. The Many Co-Authors Challenge, because the self-audit could be referred to as, aimed to flag any further work that is likely to be tainted by allegations of misconduct and, extra essential, to absolve the remaining—and Gino’s colleagues, by extension—of the wariness that now troubled the complete area.

That area was not tucked away in some sleepy nook of academia, however was as a substitute a extremely influential one dedicated to the science of success. Maybe you’ve heard that procrastination makes you extra artistic, or that you simply’re higher off having fewer decisions, or that you would be able to purchase happiness by giving issues away. All of that’s analysis carried out by Schroeder’s friends—business-school professors who apply the strategies of behavioral analysis to such topics as advertising, administration, and resolution making. In viral TED Talks and airport finest sellers, on morning reveals and late-night tv, these business-school psychologists maintain large sway. Additionally they have a presence on this journal and lots of others: Almost each enterprise tutorial who is known as on this story has been both quoted or cited by The Atlantic on a number of events. A couple of, together with Gino, have written articles for The Atlantic themselves.

Enterprise-school psychologists are students, however they aren’t taking pictures for a Nobel Prize. Their analysis doesn’t sometimes goal to unravel a social drawback; it received’t be curing anybody’s illness. It doesn’t even appear to have a lot affect on enterprise practices, and it definitely hasn’t formed the nation’s commerce. Nonetheless, its flashy findings include clear rewards: consulting gigs and audio system’ charges, to not point out lavish tutorial incomes. Beginning salaries at enterprise colleges will be $240,000 a 12 months—double what they’re at campus psychology departments, lecturers informed me.

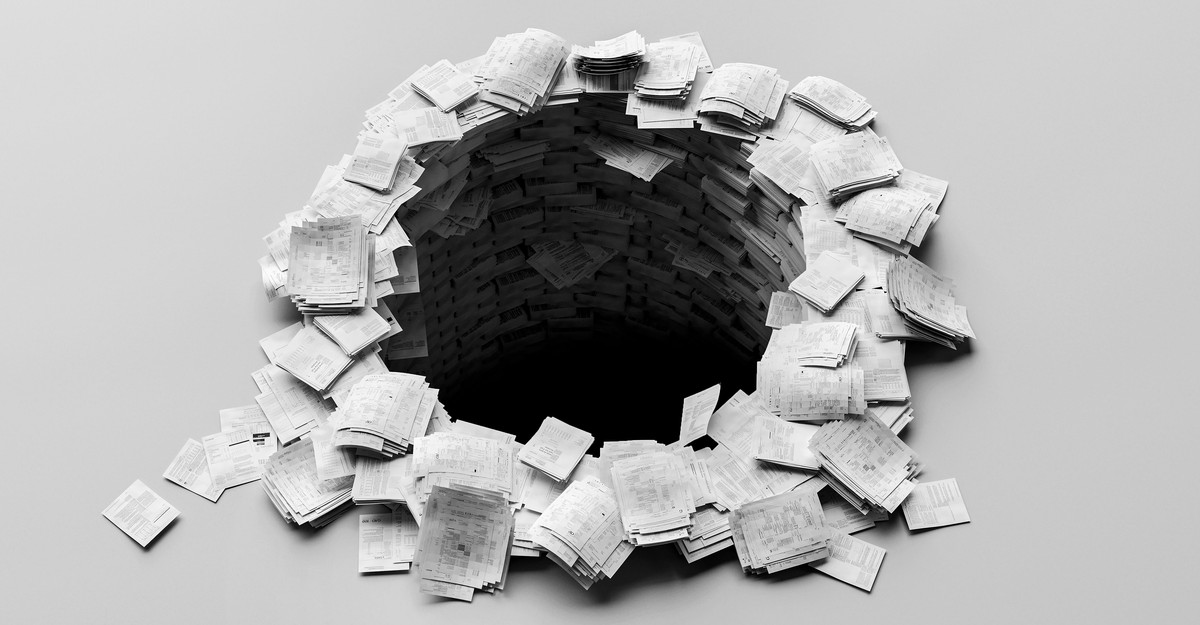

The analysis scandal that has engulfed this area goes far past the replication disaster that has plagued psychology and different disciplines in recent times. Lengthy-standing flaws in how scientific work is finished—together with inadequate pattern sizes and the sloppy software of statistics—have left massive segments of the analysis literature unsure. Many avenues of examine as soon as deemed promising turned out to be lifeless ends. Nevertheless it’s one factor to know that scientists have been slicing corners. It’s fairly one other to suspect that they’ve been creating their outcomes from scratch.

Schroeder has lengthy been thinking about belief. She’s given lectures on “constructing trust-based relationships”; she’s run experiments measuring belief in colleagues. Now she was working to rebuild the sense of belief inside her area. A variety of students have been concerned within the Many Co-Authors Challenge, however Schroeder’s dedication was singular. In October 2023, a former graduate scholar who had helped tip off the workforce of bloggers to Gino’s potential fraud wrote her personal “put up mortem” on the case. It paints Schroeder as distinctive amongst her friends: a professor who “despatched a transparent sign to the scientific neighborhood that she is taking this scandal severely.” A number of others echoed this evaluation, saying that ever because the information broke, Schroeder has been relentless—heroic, even—in her efforts to appropriate the document.

But when Schroeder deliberate to extinguish any doubts that remained, she might have aimed too excessive. Greater than a 12 months since all of this started, the proof of fraud has solely multiplied. The rot in enterprise colleges runs a lot deeper than virtually anybody had guessed, and the blame is unnervingly widespread. Ultimately, even Schroeder would turn into a suspect.

Gino was accused of faking numbers in 4 printed papers. Simply days into her digging, Schroeder uncovered one other paper that gave the impression to be affected—and it was one which she herself had helped write.

The work, titled “Don’t Cease Believing: Rituals Enhance Efficiency by Reducing Nervousness,” was printed in 2016, with Schroeder’s title listed second out of seven authors. Gino’s title was fourth. (The primary few names on a tutorial paper are sometimes organized so as of their contributions to the completed work.) The analysis it described was fairly normal for the sphere: a set of intelligent research demonstrating the worth of a life hack—one easy trick to nail your subsequent presentation. The authors had examined the concept that merely following a routine—even one as arbitrary as drawing one thing on a chunk of paper, sprinkling salt over it, and crumpling it up—may assist calm an individual’s nerves. “Though some might dismiss rituals as irrational,” the authors wrote, “those that enact rituals might effectively outperform the skeptics who forgo them.”

In fact, the skeptics have by no means had a lot buy in business-school psychology. For the higher a part of a decade, this discovering had been garnering citations—about 200, per Google Scholar. However when Schroeder appeared extra intently on the work, she realized it was questionable. In October 2023, she sketched out a few of her considerations on the Many Co-Authors Challenge web site.

The paper’s first two key experiments, marked within the textual content as Research 1a and 1b, checked out how the salt-and-paper ritual may assist college students sing a karaoke model of Journey’s “Don’t Cease Believin’ ” in a lab setting. In keeping with the paper, Research 1a discovered that individuals who did the ritual earlier than they sang reported feeling a lot much less anxious than individuals who didn’t; Research 1b confirmed that that they had decrease coronary heart charges, as measured with a pulse oximeter, than college students who didn’t.

As Schroeder famous in her October put up, the unique information of those research couldn’t be discovered. However Schroeder did have some knowledge spreadsheets for Research 1a and 1b—she’d posted them shortly after the paper had been printed, together with variations of the research’ analysis questionnaires—and she or he now wrote that “unexplained points have been recognized” in each, and that there was “uncertainty relating to the information provenance” for the latter. Schroeder’s put up didn’t elaborate, however anybody can take a look at the spreadsheets, and it doesn’t take a forensic knowledgeable to see that the numbers they report are severely amiss.

The “unexplained points” with Research 1a and 1b are legion. For one factor, the figures as reported don’t seem to match the analysis as described in different public paperwork. (For instance, the place the posted analysis questionnaire instructs the scholars to evaluate their degree of hysteria on a five-point scale, the outcomes appear to run from 2 to eight.) However the single most suspicious sample reveals up within the heart-rate knowledge. In keeping with the paper, every scholar had their pulse measured thrice: as soon as on the very begin, once more after they have been informed they’d need to sing the karaoke music, after which a 3rd time, proper earlier than the music started. I created three graphs as an example the information’s peculiarities. They depict the measured coronary heart charges for every of the 167 college students who’re mentioned to have participated within the experiment, introduced from left to proper of their numbered order on the spreadsheet. The blue and inexperienced strains, which depict the primary and second heart-rate measurements, present these values fluctuating kind of as one may anticipate for a loud sign, measured from plenty of people. However the purple line doesn’t seem like this in any respect: Slightly, the measured coronary heart charges type a collection going up, throughout a run of greater than 100 consecutive college students.

I’ve reviewed the case with a number of researchers who advised that this tidy run of values is indicative of fraud. “I see completely no purpose” the sequence in No. 3 “ought to have the order that it does,” James Heathers, a scientific-integrity investigator and an occasional Atlantic contributor, informed me. The precise that means of the sample is unclear; when you have been fabricating knowledge, you definitely wouldn’t attempt for them to seem like this. Nick Brown, a scientific-integrity researcher affiliated with Linnaeus College Sweden, guessed that the ordered values within the spreadsheet might have been cooked up after the very fact. In that case, it might need been much less essential that they fashioned a natural-wanting plot than that, when analyzed collectively, they matched faux statistics that had already been reported. “Somebody sat down and burned fairly a little bit of midnight oil,” he proposed. I requested how certain he was that this sample of outcomes was the product of deliberate tampering; “100%, 100%,” he informed me. “For my part, there is no such thing as a harmless rationalization in a universe the place fairies don’t exist.”

Schroeder herself would come to an analogous conclusion. Months later, I requested her whether or not the information have been manipulated. “I feel it’s very possible that they have been,” she mentioned. In the summertime of 2023, when she reported the findings of her audit to her fellow authors, all of them agreed that, no matter actually occurred, the work was compromised and should be retracted. However they may not attain consensus on who had been at fault. Gino didn’t seem like chargeable for both of the paper’s karaoke research. Then who was?

This is able to not appear to be a difficult query. The printed model of the paper has two lead authors who’re listed as having “contributed equally” to the work. One in every of them was Schroeder. The entire co-authors agree that she dealt with two experiments—labeled within the textual content as Research 3 and 4—through which members solved a set of math issues. The opposite major contributor was Alison Wooden Brooks, a younger professor and colleague of Gino’s at Harvard Enterprise Faculty.

From the beginning, there was each purpose to imagine that Brooks had run the research that produced the fishy knowledge. Actually they’re much like Brooks’s prior work. The identical quirky experimental setup—through which college students have been requested to put on a pulse oximeter and sing a karaoke model of “Don’t Cease Believin’ ”—seems in her dissertation from the Wharton Faculty in 2013, and she or he printed a portion of that work in a sole-authored paper the next 12 months. (Brooks herself is musically inclined, performing round Boston in a rock band.)

But regardless of all of this, Brooks informed the Many Co-Authors Challenge that she merely wasn’t certain whether or not she’d had entry to the uncooked knowledge for Research 1b, the one with the “no harmless rationalization” sample of outcomes. She additionally mentioned she didn’t know whether or not Gino performed a job in amassing them. On the latter level, Brooks’s former Ph.D. adviser, Maurice Schweitzer, expressed the identical uncertainty to the Many Co-Authors Challenge.

Loads of proof now means that this thriller was manufactured. The posted supplies for Research 1b, together with administrative information from the lab, point out that the work was carried out at Wharton, the place Brooks was in grad college on the time, learning below Schweitzer and operating one other, very comparable experiment. Additionally, the metadata for the oldest public model of the knowledge spreadsheet lists “Alison Wooden Brooks” because the final one who saved the file.

Brooks, who has printed analysis on the worth of apologies, and whose first e book—Speak: The Science of Dialog and the Artwork of Being Ourselves—is due out from Crown in January, didn’t reply to a number of requests for interviews or to an in depth checklist of written questions. Gino mentioned that she “neither collected nor analyzed the information for Research 1a or Research 1b nor was I concerned within the knowledge audit.”

If Brooks did conduct this work and oversee its knowledge, then Schroeder’s audit had produced a dire twist. The Many Co-Authors Challenge was meant to suss out Gino’s suspect work, and quarantine it from the remaining. “The purpose was to guard the harmless victims, and to search out out what’s true concerning the science that had been carried out,” Milkman informed me. However now, to all appearances, Schroeder had uncovered crooked knowledge that apparently weren’t linked to Gino. That may imply Schroeder had one other colleague who had contaminated her analysis. It could imply that her repute—and the credibility of her total area—was below menace from a number of instructions without delay.

Among the 4 analysis papers through which Gino was accused of dishonest is one concerning the human tendency to misreport information and figures for private acquire. Which is to say: She was accused of faking knowledge for a examine of when and the way individuals may faux knowledge. Amazingly, a special set of information from the similar paper had already been flagged because the product of potential fraud, two years earlier than the Gino scandal got here to gentle. The primary was contributed by Dan Ariely of Duke College—a frequent co-author of Gino’s and, like her, a celebrated knowledgeable on the psychology of telling lies. (Ariely has mentioned {that a} Duke investigation—which the college has not acknowledged—found no proof that he “falsified knowledge or knowingly used falsified knowledge.” He has additionally mentioned that the investigation “decided that I ought to have carried out extra to stop defective knowledge from being printed within the 2012 paper.”)

The existence of two apparently corrupted knowledge units was stunning: a keystone paper on the science of deception wasn’t simply invalid, however presumably a rip-off twice over. However even within the face of this ignominy, few in enterprise academia have been able to acknowledge, in the summertime of 2023, that the issue is likely to be bigger nonetheless—and that their analysis literature may effectively be overrun with fantastical outcomes.

Some students had tried to boost alarms earlier than. In 2019, Dennis Tourish, a professor on the College of Sussex Enterprise Faculty, printed a e book titled Administration Research in Disaster: Fraud, Deception and Meaningless Analysis. He cites a examine discovering that greater than a 3rd of surveyed editors at administration journals say they’ve encountered fabricated or falsified knowledge. Even that alarming price might undersell the issue, Tourish informed me, given all the misbehavior in his self-discipline that will get neglected or coated up.

Nameless surveys of assorted fields discover that roughly 2 p.c of students will admit to having fabricated, falsified, or modified knowledge not less than as soon as of their profession. However business-school psychology could also be particularly liable to misbehavior. For one factor, the sphere’s analysis requirements are weaker than these for different psychologists. In response to the replication disaster, campus psychology departments have recently taken up a raft of methodological reforms. Statistically suspect practices that have been de rigueur a dozen years in the past at the moment are unusual; pattern sizes have gotten greater; a examine’s deliberate analyses at the moment are generally written down earlier than the work is carried out. However this nice awakening has been slower to develop in business-school psychology, a number of lecturers informed me. “Nobody needs to kill the golden goose,” one early-career researcher in enterprise academia mentioned. If administration and advertising professors embraced all of psychology’s reforms, he mentioned, then lots of their most memorable, most TED Speak–ready findings would go away. “To make use of advertising lingo, we’d lose our distinctive worth proposition.”

It’s straightforward to think about how dishonest may result in extra dishonest. If business-school psychology is beset with suspect analysis, then the bar for getting printed in its flagship journals ratchets up: A examine have to be even flashier than all the opposite flashy findings if its authors wish to stand out. Such incentives transfer in just one path: Eventually, the usual instruments for torturing your knowledge will now not be sufficient. Now you must go a bit additional; now you must reduce your knowledge up, and carve them into sham outcomes. Having one or two prolific frauds round would push the bar for publishing nonetheless greater, inviting but extra corruption. (And since the work shouldn’t be precisely mind surgical procedure, nobody dies consequently.) On this means, a single self-discipline may come to seem like Main League Baseball did 20 years in the past: outlined by juiced-up stats.

Within the face of its personal dishonest scandal, MLB began screening each single participant for anabolic steroids. There isn’t any equal in science, and positively not in enterprise academia. Uri Simonsohn, a professor on the Esade Enterprise Faculty in Barcelona, is a member of the running a blog workforce, referred to as Knowledge Colada, that caught the issues in each Gino’s and Ariely’s work. (He was additionally a motivating pressure behind the Many Co-Authors Challenge.) Knowledge Colada has referred to as out different cases of sketchy work and obvious fakery throughout the area, however its efforts at detection are extremely focused. They’re additionally fairly uncommon. Crying foul on another person’s unhealthy analysis makes you out to be a troublemaker, or a member of the notional “knowledge police.” It will probably additionally carry a declare of defamation. Gino filed a $25 million defamation lawsuit towards Harvard and the Knowledge Colada workforce not lengthy after the bloggers attacked her work. (This previous September, a decide dismissed the portion of her claims that concerned the bloggers and the defamation declare towards Harvard. She nonetheless has pending claims towards the college for gender discrimination and breach of contract.) The dangers are even larger for many who don’t have tenure. A junior tutorial who accuses another person of fraud might antagonize the senior colleagues who serve on the boards and committees that make publishing choices and decide funding and job appointments.

These dangers for would-be critics reinforce an environment of complacency. “It’s embarrassing how few protections now we have towards fraud and the way straightforward it has been to idiot us,” Simonsohn mentioned in a 2023 webinar. He added, “We have now carried out nothing to stop it. Nothing.”

Like so many different scientific scandals, the one Schroeder had recognized shortly sank right into a swamp of closed-door opinions and taciturn committees. Schroeder says that Harvard Enterprise Faculty declined to analyze her proof of data-tampering, citing a coverage of not responding to allegations made greater than six years after the misconduct is alleged to have occurred. (Harvard Enterprise Faculty’s head of communications, Mark Cautela, declined to remark.) Her efforts to handle the problem by means of the College of Pennsylvania’s Workplace of Analysis Integrity likewise appeared fruitless. (A spokesperson for the Wharton Faculty wouldn’t touch upon “the existence or standing of” any investigations.)

Retractions have a means of dragging out in science publishing. This one was no exception. Maryam Kouchaki, an knowledgeable on office ethics at Northwestern College’s Kellogg Faculty of Administration and co–editor in chief of the journal that printed the “Don’t Cease Believing” paper, had first obtained the authors’ name to tug their work in August 2023. Because the anniversary of that request drew close to, Schroeder nonetheless had no concept how the suspect knowledge could be dealt with, and whether or not Brooks—or anybody else—could be held accountable.

Lastly, on October 1, the “Don’t Cease Believing” paper was faraway from the scientific literature. The journal’s printed discover laid out some primary conclusions from Schroeder’s audit: Research 1a and 1b had certainly been run by Brooks, the uncooked knowledge weren’t out there, and the posted knowledge for 1b confirmed “streaks of coronary heart price scores that have been unlikely to have occurred naturally.” Schroeder’s personal contributions to the paper have been additionally discovered to have some flaws: Knowledge factors had been dropped from her evaluation with none rationalization within the printed textual content. (Though this follow wasn’t absolutely out-of-bounds given analysis requirements on the time, the identical habits would at the moment be understood as a type of “p-hacking”—a pernicious supply of false-positive outcomes.) However the discover didn’t say whether or not the fishy numbers from Research 1b had been fabricated, not to mention by whom. Somebody apart from Brooks might have dealt with these knowledge earlier than publication, it advised. “The journal couldn’t examine this examine any additional.”

Two days later, Schroeder posted to X a hyperlink to her full and remaining audit of the paper. “It took *tons of* of hours of labor to finish this retraction,” she wrote, in a thread that described the issues in her personal experiments and Research 1a and 1b. “I’m ashamed of serving to publish this paper & how lengthy it took to determine its points,” the thread concluded. “I’m not the identical scientist I used to be 10 years in the past. I maintain myself accountable for correcting any inaccurate prior analysis findings and for updating my analysis practices to do higher.” Her friends responded by lavishing her with public reward. One colleague referred to as the self-audit “exemplary” and an “act of braveness.” A distinguished professor at Columbia Enterprise Faculty congratulated Schroeder for being “a cultural heroine, a job mannequin for the rising technology.”

However amid this celebration of her uncommon transparency, an essential and associated story had one way or the other gone unnoticed. In the midst of scouting out the perimeters of the dishonest scandal in her area, Schroeder had uncovered one more case of seeming science fraud. And this time, she’d blown the whistle on herself.

That gorgeous revelation, unaccompanied by any posts on social media, had arrived in a muffled replace to the Many Co-Authors Challenge web site. Schroeder introduced that she’d discovered “a difficulty” with yet one more paper that she’d produced with Gino. This one, “Enacting Rituals to Enhance Self-Management,” got here out in 2018 within the Journal of Character and Social Psychology; its writer checklist overlaps considerably with that of the sooner “Don’t Cease Believing” paper (although Brooks was not concerned). Like the primary, it describes a set of research that purport to indicate the facility of the ritual impact. Like the primary, it contains not less than one examine for which knowledge seem to have been altered. And like the primary, its knowledge anomalies don’t have any obvious hyperlink to Gino.

The fundamental information are specified by a doc that Schroeder put into a web-based repository, describing an inner audit that she performed with the assistance of the lead writer, Allen Ding Tian. (Tian didn’t reply to requests for remark.) The paper opens with a area experiment on girls who have been attempting to drop some pounds. Schroeder, then in grad college on the College of Chicago, oversaw the work; members have been recruited at a campus fitness center.

Half of the ladies have been instructed to carry out a ritual earlier than every meal for the following 5 days: They have been to place their meals right into a sample on their plate. The opposite half weren’t. Then Schroeder used a diet-tracking app to tally all of the meals that every girl reported consuming, and located that those within the ritual group took in about 200 fewer energy a day, on common, than the others. However in 2023, when she began digging again into this analysis, she uncovered some discrepancies. In keeping with her examine’s uncooked supplies, 9 of the ladies who reported that they’d carried out the food-arranging ritual have been listed on the information spreadsheet as being within the management group; six others have been mislabeled in the other way. When Schroeder fastened these errors for her audit, the ritual impact utterly vanished. Now it appeared as if the ladies who’d carried out the food-arranging had consumed a number of extra energy, on common, than the ladies who had not.

Errors occur in analysis; typically knowledge get blended up. These errors, although, seem like intentional. The ladies whose knowledge had been swapped match a suspicious sample: Those whose numbers might need undermined the paper’s speculation have been disproportionately affected. This isn’t a refined factor; among the many 43 girls who reported that they’d carried out the ritual, the six most prolific eaters all acquired switched into the management group. Nick Brown and James Heathers, the scientific-integrity researchers, have every tried to determine the chances that something just like the examine’s printed outcome may have been attained if the information had been switched at random. Brown’s evaluation pegged the reply at one in 1 million. “Knowledge manipulation is sensible as a proof,” he informed me. “No different rationalization is straight away apparent to me.” Heathers mentioned he felt “fairly comfy” in concluding that no matter went improper with the experiment “was a directed course of, not a random course of.”

Whether or not or not the information alterations have been intentional, their particular type—flipped circumstances for a handful of members, in a means that favored the speculation—matches up with knowledge points raised by Harvard Enterprise Faculty’s investigation into Gino’s work. Schroeder rejected that comparability after I introduced it up, however she was keen to simply accept some blame. “I couldn’t really feel worse about that paper and that examine,” she informed me. “I’m deeply ashamed of it.”

Nonetheless, she mentioned that the supply of the error wasn’t her. Her analysis assistants on the mission might have prompted the issue; Schroeder wonders in the event that they acquired confused. She mentioned that two RAs, each undergraduates, had recruited the ladies on the fitness center, and that the scene there was chaotic: Generally a number of individuals got here as much as them without delay, and the undergrads might have needed to make some modifications on the fly, adjusting which members have been being put into which group for the examine. Perhaps issues went improper from there, Schroeder mentioned. One or each RAs might need gotten ruffled as they tried to paper over inconsistencies of their record-keeping. They each knew what the experiment was meant to indicate, and the way the information should look—so it’s potential that they peeked a bit on the knowledge and reassigned the numbers in the best way that appeared appropriate. (Schroeder’s audit lays out different potentialities, however describes this one because the more than likely.)

Schroeder’s account is definitely believable, however it’s not an ideal match with all the information. For one factor, the posted knowledge point out that in most days on which the examine ran, the RAs needed to take care of solely a handful of members—typically simply two. How may they’ve gotten so bewildered?

Any additional particulars appear unlikely to emerge. The paper was formally retracted within the February subject of the journal. Schroeder has chosen to not title the RAs who helped her with the examine, and she or he informed me that she hasn’t tried to contact them. “I simply didn’t assume it was acceptable,” she mentioned. “It doesn’t look like it might assist issues in any respect.” By her account, neither one is at the moment in academia, and she or he didn’t uncover any further points when she reviewed their different work. (I reached out to greater than a dozen former RAs and lab managers who have been thanked in Schroeder’s printed papers from round this time. 5 responded to my queries; all of them denied having helped with this experiment.) Ultimately, Schroeder mentioned, she took the information on the assistants’ phrase. “I didn’t go in and alter labels,” she informed me. However she additionally mentioned repeatedly that she doesn’t assume her RAs ought to take the blame. “The accountability rests with me, proper? And so it was acceptable that I’m the one named within the retraction discover,” she mentioned. Later in our dialog, she summed up her response: “I’ve tried to hint again as finest I can what occurred, and simply be sincere.”

Across the numerous months I spent reporting this story, I’d come to think about Schroeder as a paragon of scientific rigor. She has led a seminar on “Experimental Design and Analysis Strategies” in a enterprise program with a sterling repute for its analysis requirements. She’d helped arrange the Many Co-Authors Challenge, after which pursued it as aggressively as anybody. (Simonsohn even informed me that Schroeder’s look-at-everything strategy was a bit “overboard.”) I additionally knew that she was dedicated to the dreary however essential activity of reproducing different individuals’s printed work.

As for the weight-reduction plan analysis, Schroeder had owned the awkward optics. “It appears to be like bizarre,” she informed me after we spoke in June. “It’s a bizarre error, and it appears to be like according to altering issues within the path to get a outcome.” However weirder nonetheless was how that error got here to gentle, by means of an in depth knowledge audit that she’d undertaken of her personal accord. Apparently, she’d gone to nice effort to name consideration to a damning set of information. That alone could possibly be taken as an indication of her dedication to transparency.

However within the months that adopted, I couldn’t shake the sensation that one other concept additionally match the information. Schroeder’s main rationalization for the problems in her work—An RA should have bungled the information—sounded distressingly acquainted. Francesca Gino had provided up the identical protection to Harvard’s investigators. The mere repetition of this story doesn’t imply that it’s invalid: Lab techs and assistants actually do mishandle knowledge every now and then, and so they might in fact have interaction in science fraud. However nonetheless.

As for Schroeder’s all-out concentrate on integrity, and her public efforts to police the scientific document, I got here to know that the majority of those had been adopted, abruptly, in mid-2023, shortly after the Gino scandal broke. (The model of Schroeder’s résumé that was out there on her webpage within the spring of 2023 doesn’t describe any replication tasks by any means.) That is sensible if the accusations modified the best way she thought of her area—and she or he did describe them to me as “a wake-up name.” However right here’s one other rationalization: Perhaps Schroeder noticed the Gino scandal as a warning that the information sleuths have been on the march. Maybe she figured that her personal work may find yourself being scrutinized, after which, having gamed this out, she determined to be an information sleuth herself. She’d publicly decide to reexamining her colleagues’ work, doing audits of her personal, and asking for corrections. This is able to be her play for amnesty throughout a disaster.

I spoke with Schroeder for the final time on the day earlier than Halloween. She was notably composed after I confronted her with the chance that she’d engaged in data-tampering herself. She repeated what she’d informed me months earlier than, that she positively didn’t go in and alter the numbers in her examine. And he or she rejected the concept that her self-audits had been strategic, that she’d used them to divert consideration from her personal wrongdoing. “Actually, it’s disturbing to listen to you even lay it out,” she mentioned. “As a result of I feel when you have been to take a look at my physique of labor and attempt to replicate it, I feel my hit price could be good.” She continued: “So to indicate that I’ve really been, I don’t know, doing lots of fraudulent stuff myself for a very long time, and this was a second to return clear with it? I simply don’t assume the proof bears that out.”

That wasn’t actually what I’d meant to indicate. The story I had in thoughts was extra mundane—and in a way extra tragic. I went by means of it: Maybe she’d fudged the outcomes for a examine simply a few times early in her profession, and by no means once more. Maybe she’d been dedicated, ever since, to correct scientific strategies. And maybe she actually did intend to repair some issues in her area.

Schroeder allowed that she’d been vulnerable to sure analysis practices—excluding knowledge, for instance—that at the moment are thought-about improper. So have been lots of her colleagues. In that sense, she’d been responsible of letting her judgment be distorted by the stress to succeed. However I understood what she was saying: This was not the identical as fraud.

All through our conversations, Schroeder had prevented stating outright that anybody particularly had dedicated fraud. However not all of her colleagues had been so cautious. Only a few days earlier, I’d obtained an sudden message from Maurice Schweitzer, the senior Wharton business-school professor who oversaw Alison Wooden Brooks’s “Don’t Cease Believing” analysis. Up so far, he had not responded to my request for an interview, and I figured he’d chosen to not remark for this story. However he lastly responded to a listing of written questions. It was essential for me to know, his e-mail mentioned, that Schroeder had “been concerned in knowledge tampering.” He included a hyperlink to the retraction discover for her paper on rituals and consuming. Once I requested Schweitzer to elaborate, he didn’t reply. (Schweitzer’s most up-to-date tutorial work is concentrated on the damaging results of gossip; certainly one of his papers from 2024 is titled “The Interpersonal Prices of Revealing Others’ Secrets and techniques.”)

I laid this out for Schroeder on the telephone. “Wow,” she mentioned. “That’s unlucky that he would say that.” She went silent for a very long time. “Yeah, I’m unhappy he’s saying that.”

One other lengthy silence adopted. “I feel that the narrative that you simply laid out, Dan, goes to need to be a risk,” she mentioned. “I don’t assume there’s a means I can refute it, however I do know what the reality is, and I feel I did the correct factor, with attempting to wash the literature as a lot as I may.”

That is all too typically the place these tales finish: A researcher will say that no matter actually occurred should endlessly be obscure. Dan Ariely informed Enterprise Insider in February 2024 : “I’ve spent an enormous a part of the final two years looking for out what occurred. I haven’t been capable of … I made a decision I’ve to maneuver on with my life.” Schweitzer informed me that probably the most related recordsdata for the “Don’t Cease Believing” paper are “lengthy gone,” and that the chain of custody for its knowledge merely can’t be tracked. (The Wharton Faculty agreed, telling me that it “doesn’t possess the requested knowledge” for Research 1b, “because it falls exterior its present knowledge retention interval.”) And now Schroeder had landed on an analogous place.

It’s uncomfortable for a scientist to say that the reality is likely to be unknowable, simply as it might be for a journalist, or some other truth-seeker by vocation. I daresay the information relating to all of those circumstances might but be amenable to additional inquiry. The uncooked knowledge from Research 1b should exist, someplace; in that case, one may examine them with the posted spreadsheet to substantiate that sure numbers had been altered. And Schroeder says she has the names of the RAs who labored on her weight-reduction plan experiment; in concept, she may ask these individuals for his or her recollections of what occurred. If figures aren’t checked, or questions aren’t requested, it’s by selection.

What feels out of attain shouldn’t be a lot the reality of any set of allegations, however their penalties. Gino has been positioned on administrative go away, however in lots of different cases of suspected fraud, nothing occurs. Each Brooks and Schroeder seem like untouched. “The issue is that journal editors and establishments will be extra involved with their very own status and repute than discovering out the reality,” Dennis Tourish, on the College of Sussex Enterprise Faculty, informed me. “It may be simpler to hope that this all simply goes away and blows over and that any individual else will take care of it.”

Some extent of disillusionment was frequent among the many lecturers I spoke with for this story. The early-career researcher in enterprise academia informed me that he has an “unhealthy interest” of discovering manipulated knowledge. However now, he mentioned, he’s giving up the combat. “Not less than in the interim, I’m carried out,” he informed me. “Feeling like Sisyphus isn’t probably the most fulfilling expertise.” A administration professor who has adopted all of those circumstances very intently gave this evaluation: “I might say that mistrust characterizes many individuals within the area—it’s all very miserable and demotivating.”

It’s potential that nobody is extra depressed and demotivated, at this level, than Juliana Schroeder. “To be sincere with you, I’ve had some very low moments the place I’m like, ‘Nicely, perhaps this isn’t the correct area for me, and I shouldn’t be in it,’ ” she mentioned. “And to even have any errors in any of my papers is extremely embarrassing, not to mention one that appears like data-tampering.”

I requested her if there was something extra she needed to say.

“I assume I simply wish to advocate for empathy and transparency—perhaps even in that order. Scientists are imperfect individuals, and we have to do higher, and we will do higher.” Even the Many Co-Authors Challenge, she mentioned, has been an enormous missed alternative. “It was kind of like a second the place everybody may have carried out self-reflection. Everybody may have checked out their papers and carried out the train I did. And folks didn’t.”

Perhaps the scenario in her area would finally enhance, she mentioned. “The optimistic level is, within the lengthy arc of issues, we’ll self-correct, even when now we have no incentive to retract or take accountability.”

“Do you consider that?” I requested.

“On my optimistic days, I consider it.”

“Is at the moment an optimistic day?”

“Not likely.”

This text seems within the January 2025 print version with the headline “The Fraudulent Science of Success.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/vwt-recovery-shoes-may-24-test-oofos-mens-ooriginal-sandals-kyle-wegner-15-c0bbb74ece4b42069b11d6478148a13a.jpeg)